“…One day, I will be able to get out of this calamity.”

25-yr-old asylum seeker (undisclosed country). Detained for 2 years and 2 months.

United States

American Gulag, Part 2

“I was hunted by my government,” he explained to me.

The man was 33-yrs-old, and he was from Cameroon. He asked I withhold his name for safety reasons.

“My life was in danger so I smuggled myself out of Cameroon to Nigeria. I took a flight out of Nigeria to Ecuador. From Ecuador, I moved to Colombia. From Colombia, I moved to Panama. Panama to Costa Rica. Costa Rica to Nicaragua. Nicaragua to Honduras. Honduras to Guatemala. Guatemala to Mexico. In Mexico, I was in a detention center for close to 7 days. In Mexico, I told them, I’m moving to the US, where I knew I was going to have international protection…That’s how I found myself at the US port of entry in El Paso. I knew if I got to America, I would be safe. That’s why I had to take that journey to get to the Texas point of entry.”

Each year, thousands of men, women and children approach a US border point of entry or find other ways into the United States to claim asylum. Each one has a unique history and story. Unfortunately, their histories and stories often get exploited for political interests and agendas or get lost in ever-changing headlines.

What is reality and what is myth?

The reality is….They have been hunted by oppressive governments. They have been targeted because they are from LGBTQ communities. They have been threatened by pervasive gang violence. They have endured years of domestic abuse. They have fled war and armed conflict, and they have escaped from paralyzing poverty and failed states. Their personal stories are usually filled with trauma and violence, loss and desperation, fear and exhaustion. But they are also filled with resilience and survival as well as hope. The myth is: to reach the US, means you’ve reached safety. To reach the US, your human rights and dignity will be respected. To reach the US, you will be protected. To reach the US, you can finally escape the horrors of the place where you were fleeing from.

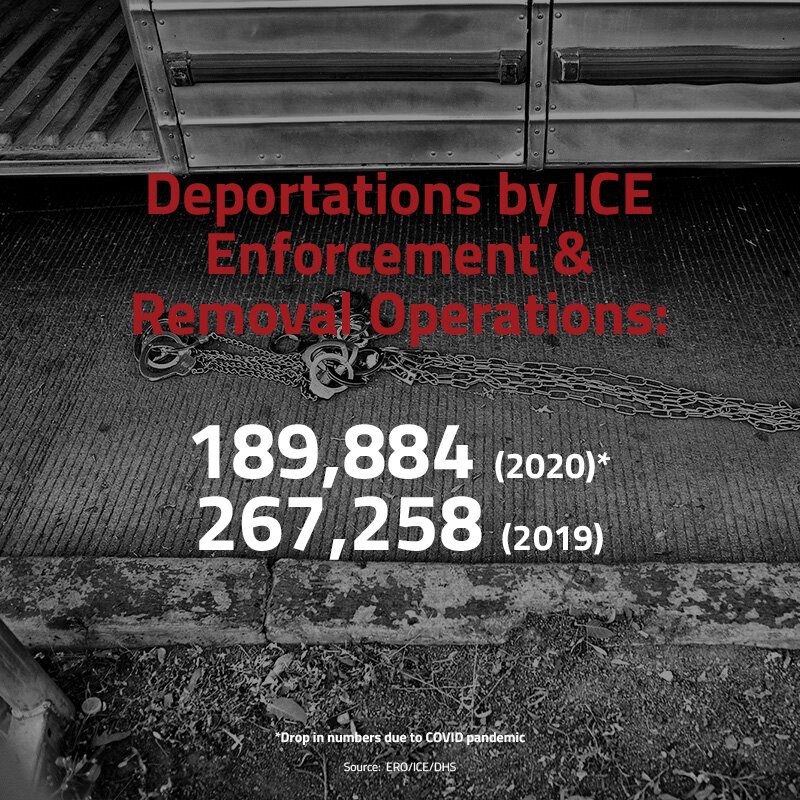

In early 2017, the Trump Administration launched an assault on immigrants who turned to the US for safety, sanctuary and asylum. Every year the Trump Administration issued executive orders, policy changes and legal tactics meant to target immigrant communities and dismantle the US asylum system.

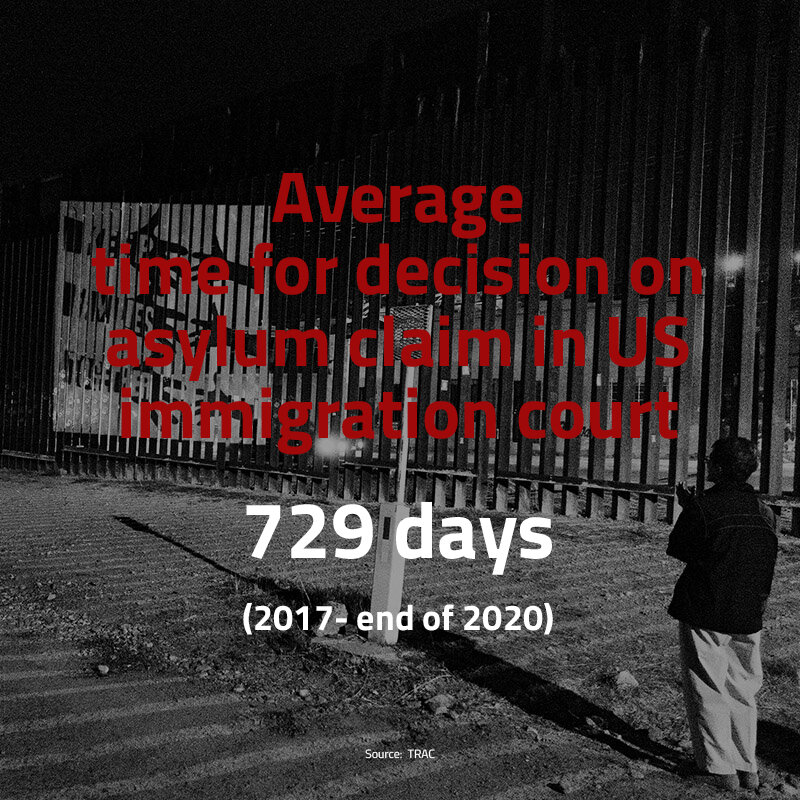

One of the most destructive components of these policies was the massive increase of people being detained inside the labyrinth of immigration detention prisons scattered throughout the United States. In the four years of Trump, more people than ever were forced to languish in detention for months and often years for ‘administrative reasons’, fighting against deportation as their asylum claims slowly made their way through the overwhelmed immigration courts.

The United States has the largest immigration detention system in the world. Most are owned and operated by private prison corporations like GEO Group and CoreCivic, Inc. Presidents Reagan, Bush Sr., Clinton, Bush Jr. and Obama all contributed to the expansion of the US immigration detention system. Yet, the Trump administration used immigration detention with an intensity unlike any of his predecessors.

American Gulag, Part 2 is the second of three extensive photo-testimonial essays in the Seven Doors project exposing the impact immigration detention has on individuals and communities in the United States. The work focuses specifically on the west coast and southern border and comes as a result of hours of interviews and several extensive road trips along the west coast and southern border. American Gulag, Part 1 provided a new translation of the geography of the vast system of detention prisons scattered across the perimeter of the US. Both of these essays aim to provide a collective testimony of the personal and painful experience of immigration detention.

What happened to this 33-yr-old, educated man from Cameroon after he had travelled over 11,000 miles to asked a Customs and Border Protection officer for asylum at the point of entry in El Paso?

We spoke for over an hour. He described how he spent one year and three months in two different immigration detention prisons. The first located in El Paso, Texas. The second in a for-profit immigration detention prison located in a remote, isolated section of the desert in New Mexico. He explained how he couldn’t afford to pay a lawyer and said he had no other option but to represent himself. He described how in detention he prepared his case and navigated the overwhelmingly complex legal process. He presented his story and asylum request to different judges in different jurisdictions within the immigration courts. He spent more months appealing their decisions.

His efforts were unsuccessful. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deported him back to Cameroon. He said to me,

“So, I and my family, we are in hiding right now.”

“Some of our lives have already been destroyed because of what we went through in our countries.”

“And they keep us in detention for over a year, or three years or some people four years, and you end up deporting a person empty handed to a country where they are in fear of being persecuted! They destroy you. The system is meant to frustrate people and to just get them out of the United States by whatever way they can do it.”

38-yr-old asylum seeker from Sierra Leone. Detained 1 year and 8 months.

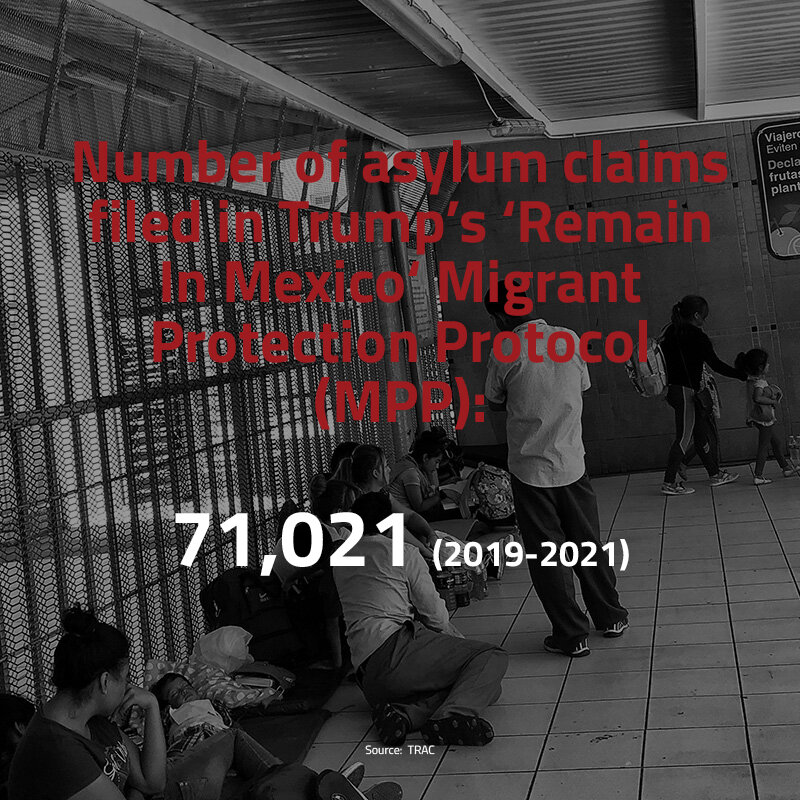

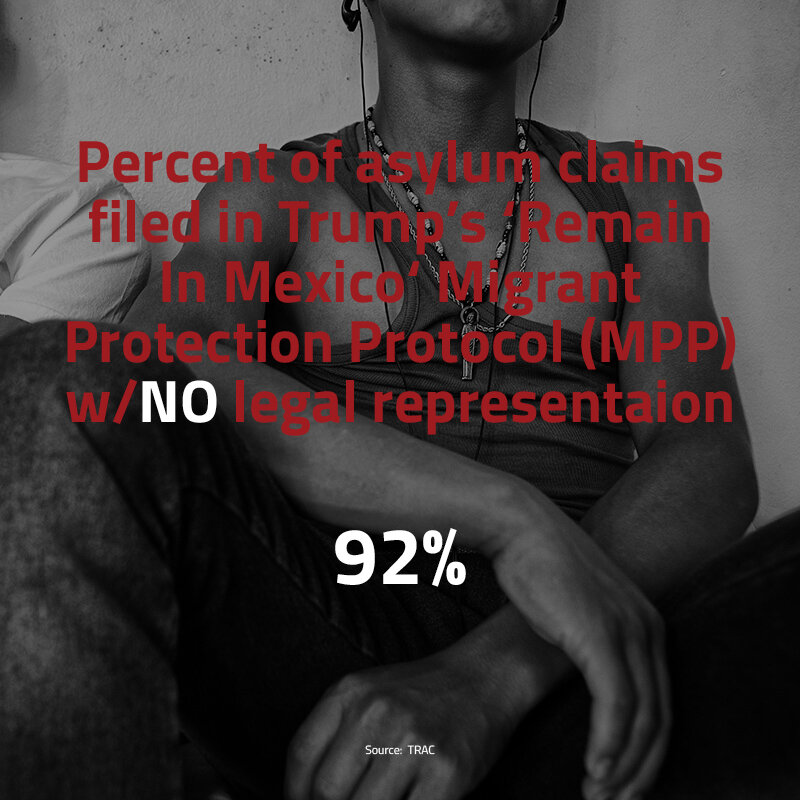

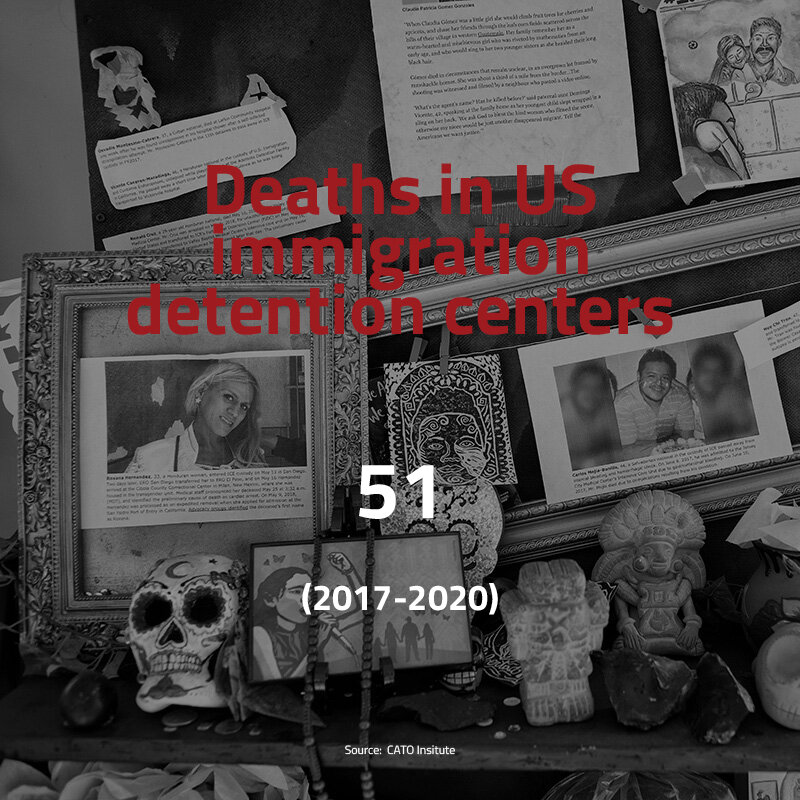

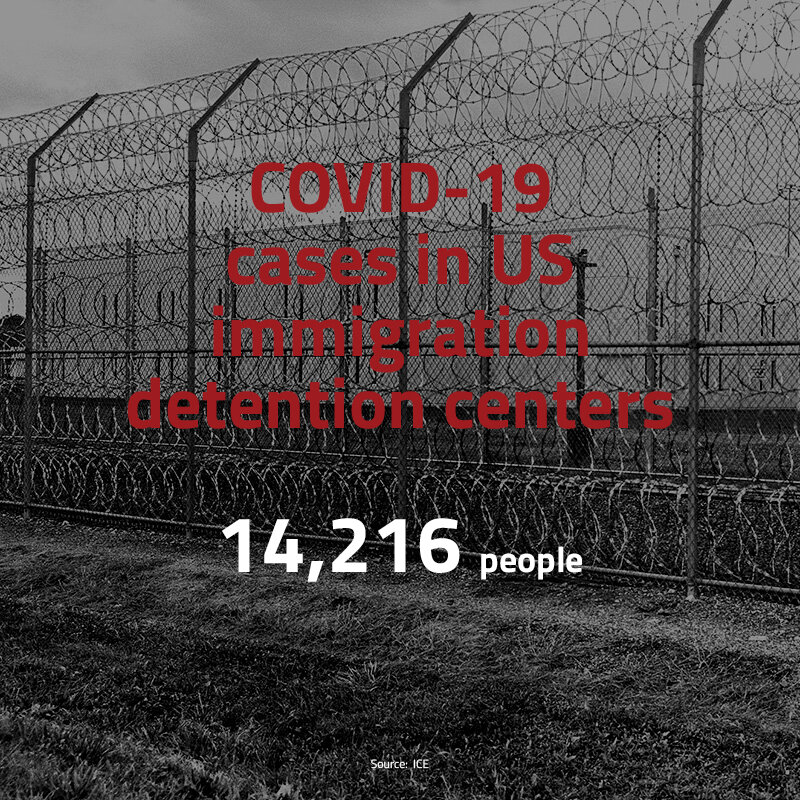

THE NUMBERS

"My husband was killed and one of my sons kidnapped and I haven't heard from him since. For a time, I didn't know if he was dead or alive, but it has been a long time and I assume he is dead.”

“We went to all the newsstands and looked at the papers to see if anyone had found a dead body like my son. Every day we would look in the newspapers. I would go by the morgue all the time. Then one day I received a text message telling me to stop visiting the morgue. Stop looking. You will never find your kid again.

This 45-year-old woman waits with her daughter-in-law and two grandchildren in Nogales, Sonora to claim asylum at the Nogales port of entry in Arizona. They've waited two weeks at the border to have their asylum claims heard.

“There was no way we could stay. We came here to the border and want to enter the US. My mother told us to not even consider going back home so we have to stay here. We just want to be safe. I have all the proof they will need, and we hope it will be enough for them to permit us to stay and have our asylum claim heard.

“My grandchildren ask for him every day. When we left we said we were going on a vacation. My grandson said he didn’t like the vacation. My granddaughter thinks where we are going is where her father is.”

Having recently fled death threats and violence from gangs in their hometowns, this 16-yr-old and 17-yr-old left Guatemala and arrived at the US border in Nogales, AZ as unaccompanied minors.

"The gangs were asking me to join and if I didn’t they said they would kill me. All of this started about four weeks ago. I was in fear for my life. I made the trip through Mexico all by myself. I want to claim asylum in the US and join some family in Florida, but I have no idea about detention and what will happen."

A 37-yr-old mother holds her 2-yr-old daughter while sitting on the sidewalk with other family members at the US port of entry in Nogales, Arizona. Over the course of two years, two attempts were made to kill her husband. The family has already waited two weeks for US Border Protection to hear their asylum claim.

“We have a big fear of being separated. We think my husband will be separated from us. The lawyers said it might happen. But we are willing to take the risk."

After US Customs & Border Patrol made them wait several weeks on the Mexican side of the US border, a group of women and children prepare to enter through the border gates where they will claim asylum to US border officials.

“After I lost my baby, they gave me my credible fear interview. I wasn’t well.

“I was dealing with my brother’s death and I was dealing with my baby’s death. They didn’t give me the opportunity to talk to a lawyer. I did it by myself. They didn’t believe my story.”

“When I turned myself in at the border I told them I was pregnant. The people at immigration claimed that everything I told them was a lie. I told them about my brother being killed and I was afraid for my life because I was being threatened. They started laughing at me and said that everyone comes to them with the same story.

“When I turned myself in, I started feeling sick and I told them that I needed help, and they did nothing. There were a lot of people in the same room. They all started to get worried about me because I was bleeding. They called the officers, but nobody came. The next day I was transported to Otay Mesa Detention Center and they didn’t provide me any medical assistance. Nine days later, they told me that I had just lost my baby.

“There are so many restrictions in detention. You cannot hug another detainee. If you see someone crying you cannot help them or hug them. There is no privacy in your room. There are cameras everyone. You cannot talk about your case with anyone. You cannot contact your family when you want to. When you go to eat, there are guards everywhere. Once a week when you go outside, there are guards everywhere. If we want to go to the church or see our lawyers, we always have to be guarded by someone. You can’t do anything by yourself.

“They put this bracelet on me the day I was let out. It hurts when I wear it. It still feels like I am detained. I have to worry about it all the time. When they take it off, I will still feel like I have it on.”

22-year-old asylum seeker from El Salvador. Detained for 6 months.

“The gangs said, You are either with us, or you are against us! I spent several months in Mexico but it was not safe. I was five months pregnant when I presented myself at the US border to claim asylum.

“They put handcuffs on me and a chain around my belly. I thought, I’ve made a big mistake.

“There are a lot of people in detention who instead of helping you, they tell you things that make you more scared. They would tell me that I wouldn’t get out until I had my baby in there. I was in detention for one month and one week. I was fortunate, but if I had known how they treated pregnant women in detention, I don’t think I would have come. It was terrible.“

31-year-old asylum seeker from El Salvador and her 2 month old baby. Detained for five weeks.

“Most of the time in detention, it’s like you are in the military. Anywhere you go in the detention center you have to walk and stand with your hands behind your back. I still find myself walking around with my hands behind my back.

“When I got out, ICE said they had to put a GPS on my leg. They said not to break the rules. Follow my appointments and they wanted to see my movement. I was just, Let me out of these chains. Let me out of El Centro.

“After I was released, I went to the mosque to pray and the bracelet started like screaming and vibrating, Battery Low, Recharge Unit! People beside me and in front of me were all looking at me. People were afraid I would cause problems for others in the mosque. I stopped going to the mosque.

“I got a job driving and delivering packages. Two weeks into the job, I had to deliver something outside of the city. On my way there, the GPS started making noise saying I needed to Recharge. With the delivery, I had to make the delivery at a specific time. I was so scared about the GPS, if something went wrong with it, would I get arrested or sent back to detention? I couldn’t make the delivery. I had to go back home because I was told that the bracelet can’t have a low battery. I was fired from the job.

“The bracelet is another version of being in detention. I can get out in the sun now, but I’m still in detention.“

25-yr-old asylum seeker from Somalia. Detained for 7 months.

“Back home, people looked up to me. My kids did. My family did. The people in my community did…

“Life is more than you actually see. I didn’t choose to leave. I had a job there. I was forced to leave. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be alive today. The gangs told me that I would only have until the end of the year to live. I knew what they were capable of. I knew I had to go.

“At the moment I first entered the detention center, I literally had no idea of what was going to happen. I made up my mind to face whatever situation would be. My mind was ready but when I got there, it was like a totally different thing. My freedom was gone, just like that. And it took a toll on me. I was in detention for 7 months and I was totally traumatized.

“I was emotional and sad. I’m in a place where I never thought I would be…in a jail. I didn’t know this is what I would have to do. My emotions went wild. It was Christmas. I missed my kids. I was trying to process, Is this really what I want?”

32-yr-old asylum seeker. Detained for 7 months

“They moved me from the border, to San Diego. Then to Arizona. Then to New York. Then to California. It was very confusing and frustrating. They wouldn’t tell me why. I was handcuffed from place to place. It felt like I was being kidnapped from one place to another.”

19-yr-old asylum seeker from Guatemala. Detained for 18 months

“In Honduras, the gangs are always looking for transgender people to kidnap for prostitution or to carry drugs or worse. It got to a point where I was afraid for myself and my family so one night I just left. I put on a small backpack, and I didn’t say goodbye to anyone. It was so hard leaving my family and not saying goodbye to them. I called them after I arrived in Mexico. In Mexico, I faced the same level of discrimination from the cartels. I received so many threats in Mexico, I had to leave.

“At first I thought it would be a short detention in the US. I faced a lot of sexual abuse in detention. I was sexually assaulted and I complained. There was a guard who saw everything and didn’t do anything about it. I tried to call a help line but the people at the detention center disconnected my call and threatened to put me in solitary if I tried to call again…They try to abuse you so much you then want to sign your own deportation. I almost got to that point.

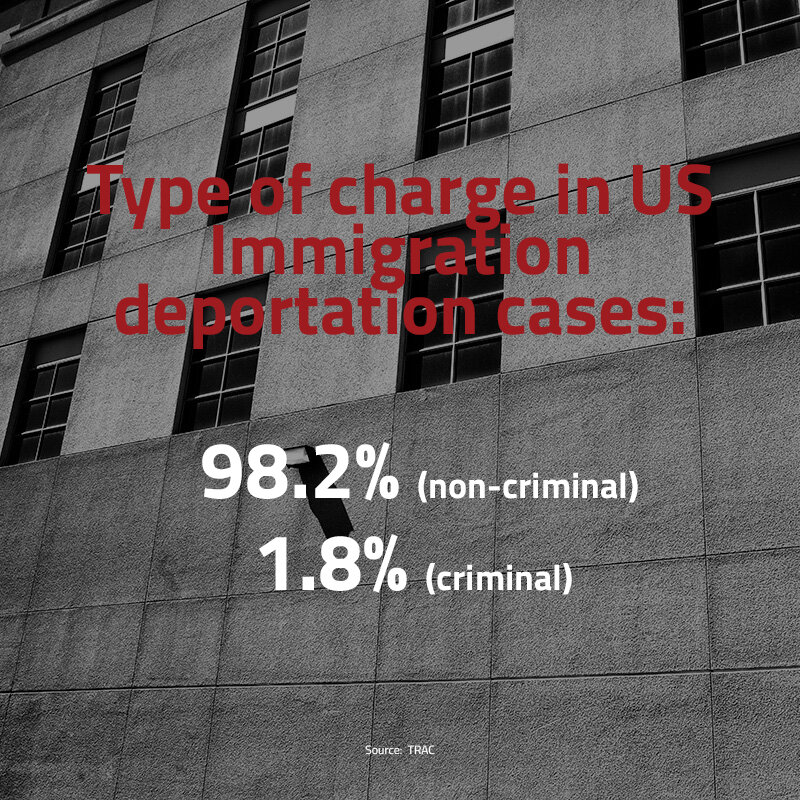

After I got out of detention, I still feel like I’m being treated like a criminal. I’ve never committed a crime. I’ve never done anything, but still in society I walk around with a monitor. People call you a criminal. They know criminals wear these things. But, I’m not a criminal.”

24-yr-old, transgender woman seeking asylum from Honduras. Detained for 9 months.

“At home in El Salvador, the gangs wanted my younger brother to join. They beat him up and threatened him. They harassed me as well. When my brother refused to join the gang, they tried to kill him. Then one day, my father left for work and he never came home. A woman said she saw two men grab him on the street and take him away in a car. We never saw him again.

“I was two months pregnant when I was put in detention. I had an exam and the doctor in the detention center said my child had Down Syndrome. They gave me no other specific information. They just said, We're sorry. It was devastating. It traumatized me. I became so depressed. Then they sent me to a hospital outside the detention center. They were so nice and they said my baby didn't have Down Syndrome. But by then, they had already psychologically damaged me. When I came out, I was always traumatized by that.

“In detention, they have a strategy and that is to make people psychologically desperate. They did it to me.”

24-year-old woman seeking asylum from El Salvador. Detained for 4 months.

A mother with her three children, along with volunteers from a faith-based visitation program out of Los Angeles, pray together in the parking lot of the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in Adelanto, CA. The father has been in immigration detention for almost three years.

“For people or families who visit, the emotional and physical journey of going out to the detention center…it wears on them. You get tired.

“The ups and downs emotionally of preparing yourself to see someone in a uniform who is in detention and how the look on their face changes over time wears on families. It gets to the point where some just can’t continue going. They stop. And for the person inside it is the same. They are in there for months, not knowing how their asylum claim is going to turn out. They keep trying and trying. But for many, after a while, it becomes too much for them.

“Their journey of waiting and waiting and being isolated from everyone wears on them and it gets to the point where they often just can’t take it anymore. And they too lose hope and stop. They sign their deportations. Their journey and the journey for those families who try to come visit them, the challenges they both face resemble each other. It’s incredibly sad.”

Eldaah, Visitation program director

Karnes County Residential Center is located in Karnes, TX . The facility was one three detention centers across the country used specifically for the detention of families. In 2020, the facility was used exclusively to detain families before they were deported under the highly controversial public health "Title 42”, which the Trump administration created as an expedited way to expel migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Migrants were denied the right to due process and an opportunity to have their cases heard. Between March 2020 and October 2020 over 200,000 people were expelled from the US under Title 42.

“They didn’t give me any explanation why we were being separated. Three days after we were separated I was taken to testify before the judge and my son wasn’t there.“

“When I saw the judge I asked him, Why are they separating families? I told him I thought it was very wrong that they were separating families. The judge said, I agree it is bad but we will reunite you guys at a certain place.”

Bernabe, 45-yr-old asylum seeker from Honduras

Separated from his 15-yr-old son in May 2018 for 2 months

Detained for 6 months (4 months with his son)

I miss you Mama

I love you a lot

Me and you have to be strong Mama

I want you to get out soon Mama because I miss you

I love you a lot

I also miss my little siblings

But we have to be strong Mama

Originally from Guatemala, this 41-year-old man was separated from his 14-year-old daughter by CBP and ICE when they crossed into Arizona. They were separated for over two months. The day after they were reunited they wait for a bus at the Phoenix Greyhound Station. They will stay with family in California while their asylum case is processed.

“They separated us at the border and I had no idea it was going to be this long.”

“They took me to Eloy and she was taken somewhere in Texas. I cried all the time. They gave us no information about how long we would be separated or when I would see her again. I didn’t know what was going on. My heart sunk when we saw each other.“

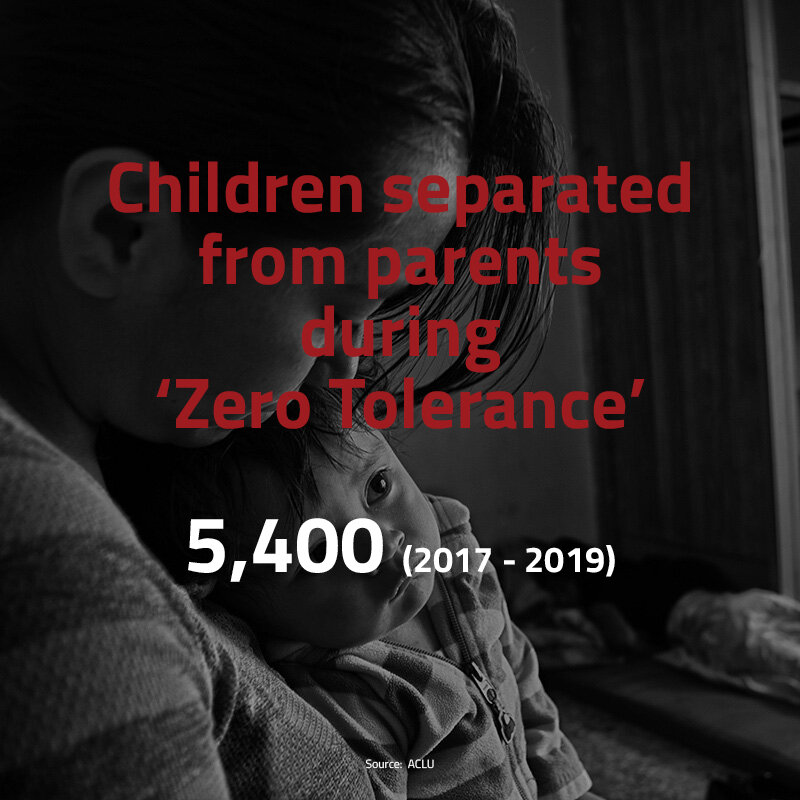

In a rented office in downtown El Paso, a group of volunteer lawyers work late into the evening of July 26, 2018. The lawyers have flown in from all over the country to manage the intake of hundreds the families reunified before the court ordered deadline of July 26th. The Trump Administration was ordered to reunify thousands of immigrant children age 5 and older who were separated from their parents at the border as a result of the ‘Zero Tolerance Policy’.

(Top left) With only one day left to meet the deadline to reunite separated families, case workers assigned to a group of unaccompanied minors follow two 'Disaster Case Managers' up an escalator at the El Paso Airport. (Top Right) After arriving from locations around the country, several boys enter into a van at the El Paso Airport. Over 2551 children over the age of 5 who had been separated from their parents as a result of Zero Tolerance policy were eligible for reunification with their parents as part of a court order. (Lower left) A group of families recently reunited gather in front of Departure/Arrival monitors at the El Paso Airport. (Lower right) Two case workers escort a group of four unaccompanied minors to their departing flights at the El Paso Airport.

TORNILLO TENT CITY was a children’s immigration shelter created in the desert on the US/Mexico border wall at Tornillo, Texas. Operated by the non-profit company, BCFS Health & Human Services it had a capacity of 1,575 children, yet in December 2018, it held up to 3,000 kids. From June 2018 to mid-January 2019 some 6,000 children where held here. The facility closed in mid-January 2019

“I could not afford a lawyer. Nobody informed me of anything. My deportation officer, nothing. The ICE attorney, nothing. It was like they were imposing something on me.

“On the day of my first hearing, the judge told me clean and clear, The United States doesn’t want immigrants at this moment.”

“It was Judge Abbott who said that. The day of my master hearing, I was the only African guy there and I was the only person who could understand English. The rest were Latin American guys. The judge said, Your case to seek asylum is not an easy case for you. The system only wants deportation. It was clear.”

33-yr-old asylum seeker from Cameroon. Detained 1 year and 3 months.

Portraits of various Judges cover a wall outside the William D Browning Special Proceedings Courtroom at the US District Court in Tucson, AZ. Operation Streamline proceedings in Tucson began in 2008.

On July 9th, 2018 the Southern District Court in San Diego took its first mass immigration hearing as part of ‘Operation Streamline’. The assembly-line style hearings served as an expedited prosecution process that were highly controversial. Operation Streamline was started in 2005 during the Bush Administration. As a result of 'Zero Tolerance’ policy in April 2018, the San Diego court was the last court on the southern border to initiate the process. An immigration defense lawyer enters into Courtroom 2A in the Southern District Court in San Diego on July 16, 2018 where Federal Magistrate Judge Jan M. Adler would preside over one of California's first Operation Streamline hearings. Over the course of just a few hours, fifty-one defendants would be tried and sentenced for illegal entry. Lawyers were given only 30 minutes to meet with their clients prior to the proceedings.

Operation Streamline Court Proceeding

Southern District of California, San Diego

July 16, 2018

5:30pm

Immigration Defense Lawyer:

“Your Honor, before I start talking over particular circumstances, I would like to object to all of the individuals, what I can count are 19 total, being brought out in leg restraints today.

“…I ask they be taken out of the court and brought back into the courtroom without leg restraints. There are on my account five US Marshals at one entrance and three more at the other entrance and another US Marshal at the court entrance...

Federal Magistrate Judge, Jan M. Adler:

“I wish to address to the issue of restraints. Does the government wish to respond?”

Government Attorney:

“Yes your honor…we feel that under the circumstances with the number of individuals and limited security available and in fact, basically unless you are standing right over there, you can't see if they are shackled or not. I feel this would have no real import on the court’s decision and I don’t think your Honor can see them [shackles] from where you are and you’re elevated. I see no problem. Your Honor’s decision to shackle was appropriate and we would encourage them to remain.”

Immigration Defense Lawyer #2:

“Thank you your Honor. The Government’s comment reflects the consistent misunderstanding of the nature of shackling. It is not about whether the court can see them. It’s about the dignity and decorum that these individuals appear before the court.”

Immigration Defense Lawyer:

“Your Honor, I am concerned that this process has forced me to render insufficient counsel to my client. All of our clients were not brought in until 9:35am. I saw my first client at 9:40. The man before you was my fourth client and I had very little time to spend with him, because the one single phone available for non-Spanish translation became available, which meant I needed to interrupt my initial meeting with this client so I could use this telephone to talk with me third client who is Punjabi. The telephonic translation was difficult because there is only a single phone, so that process took a lot of time for me. I was left with very little time to talk with this client…we spoke for only approximately 20 minutes.”

Door to the William D Browning Special Proceedings Courtroom at the US District Court in Tucson, AZ. On this day, June 26, 2018, over 50 immigration detainees were prosecuted and sentenced as part of Operation Streamline.

“I am now waiting for a hearing, which will determine if I will win my Asylum or get another relief, in God’s will…I have been in more than 13 courts since I started my immigration processes and still more to come.”

25-yr-old asylum seeker (undisclosed country). Detained for 2 years and 2 months

A bus from the Pinal County Sheriff's Department drives away after dropping off detainees at the Eloy Immigration Detention Center in Eloy, Arizona.

Row 1: Otay Mesa Detention Center, San Diego; El Paso ICE Processing Center; Florence Service Processing Center, Florence, AZ; Row 2: Otero Processing Center, Chaparral, NM; Imperial Detention Center, Calexico, CA; Northwest Center Center, Tacoma, WA; Row 3: T. Don Hutto Residential Center, Taylor, TX; Florence CCA, Florence, AZ; Val Verde Detention Center, Del Rio, TX; Row 4: San Luis Detention Center, San Luis, AZ; Tornillo Tent Camp, Tornillo, TX; Karnes County Residential Center, Karnes, TX; Row 5: Eloy Detention Center, Eloy, AZ; South Texas Detention Center, Persall, TX; West Texas Detention Center, Sierra Blanca, TX.

“In detention, I had to set my mind to separate myself from the world, because thinking about things was making it worse...just thinking and thinking.

“The reality forces you to separate yourself sometimes from the world and accept where you are at, because if not, those walls kind of take over.”

Erica, Detained for 8 months

Late at night, a group of men walk up from the underground garage of the US Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles. All were brought to Los Angeles from detention centers in Orange County, CA after being recently released from ICE custody.

“My family is from Vietnam. When my father reported to immigration, ICE arrested him. We had no idea. It was a total surprise. He was in detention for months. We paid the huge bond and were told he would be released so we drove down from San Francisco to pick him up.”

Daughter of man being released from detention at US Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles.

Two of Liz’s children riding on bicycles at the church where they have lived in sanctuary for over a year outside of Phoenix, AZ.

“ICE can come to your home at any time. I had a job. I’m paying taxes. I’ve tried to build credit to buy a house. I have a bank account. I’ve lived here my whole life. I had a past but I didn’t hurt anyone and I paid for all that. I’m a good person. I’m making something out of my life. My kids are US citizens. They are enrolled in school and playing sports. And for ICE to take this from me. ICE gave me seven days to show proof of who my kids would stay with in case I was deported. Thanksgiving was coming up and I thought, God let me see through this. My daughter had a basketball game. I was so happy to see her play.

“I was supposed to go to the ICE office the day after the game. But people helping me, said to me, There is a church we want you to go to.

“If ICE forces my kids to go to someone if I was detained, they don’t see how there is anything wrong. They don’t see the damage they are doing and they are not held to account for it. They think that by placing my kids with other people just because they want me is OK.

“I was brought here to the US when I was 11 months old. I’m from the US. I’ve been here all my life. It hurts me to have to do this, but this is the only way I can survive.

“My kids depend on me. ICE doesn’t see them. They don’t see the harm they are doing to my kids. They don’t see them hurt. If they have me, they don’t care about anything else. All ICE focuses on is trying to detain me.”

Liz, January 2019. She and her children had already spent one year in refuge and sanctuary in a church outside of Phoenix, AZ.

“Most women had no idea they would be treated like criminals…These are women who are survivors of really tough and traumatic incidents and they are being held indefinitely away from their families with no bond for offenses that are not violent. For offenses that are not hurting anyone. They are taking people from their homes and putting them into detention for no reason.

“When the DOJ is creating legislation that is going to criminalize people through the immigration system, it’s a double jeopardy for folks. Undocumented people go through the justice system separately. At the end of the day, most of the people being held indefinitely are people who had not committed a violent crime at all.

“Officers are not sensitive to immigrant folks and people coming from other countries and understanding why people come and ask for refuge. They do what they want to do. It’s awful. They make it hard for women to get bonds and go back to their families. They force women to give up their rights. Most women go to the court alone because none of their family members can come. They slowly become invisible. They don’t want us to talk to each other or any other people. When you make it hard for people to visit, when you make it really expensive and there are privatized phone calls, the women feel more and more invisible.

“But you know the women inside are resilient. They know who the real enemy is and it’s not the other women inside.”

“I left Guatemala when I was 14-years-old because of the gangs. I was in Mexico but had to leave there too.

“I spent my 18th birthday in detention. It was the worst birthday of my life. I felt terrible and so sad. During the entire time I was in detention I thought of all those things I should be doing as a young man. I felt helpless. A feeling of sadness comes over you.”

19-yr-old asylum seeker from Guatemala. Detained for 18 months.

“After I turned myself in at the point of entry, I spent the weekend in the doghouse and then they said, You’re leaving. They took me to Phoenix for a week, then to El Paso, then to New Mexico, then back to El Paso where I spent another eight months. It was the worst experience of my life.

“I left El Salvador because they wanted to kill me because of my sexual orientation. I also had problems in Mexico. I was running from humiliation and I was threatened in both places. I came looking for protection but I don’t believe I’ve found it here either.“

Jose, 21-yr-old asylum seekers from El Salvador. Detained for 9 months

“Gangs killed my sister. I witnessed the killing so I knew I had to leave. When I was walking towards the border, I felt relieved because I had spent one year traveling from El Salvador to the US border. The first time I approached the officers at the point of entry to claim asylum they said, No. The second and third times they took me back to Mexico side and told me to wait.

“As soon as I was detained, my hands and feet were cuffed and I had a chain around my waist. I was transferred from California to Arizona then back to California. I was handcuffed the entire time. I spent 10 months in detention. At times, I still feel like I’m in detention. When I was there, they controlled everything I did. When I was released, they still control what I do. They are still on top of me.“

20-yr-old asylum seeker from El Salvador. Detained for 10 months.

“They are released from detention and ICE just dumps them off at the bus station. They are shell-shocked and they are weary and scared because of what they have gone through in those places. They have nothing. We’re here to help them.”

Volunteer of Interfaith Welcome Coalition, San Antonio, TX

Backpacks filled with snack food, hygiene products, water and other essentials are placed in the lobby of a local church a few blocks away from the Greyhound bus station in downtown San Antonio. Volunteers of the Interfaith Welcome Coalition prepare hundreds of backpacks each month and provide them to individuals (mostly families) recently released from immigration detention centers in Karnes and Dilley, Texas. Immigration releases the families and individuals from detention without any support, leaving it up to small organizations to provide crucial personal and logistical assistance.

A woman from Honduras lifts up her baby at a shelter in Tucson, AZ. Cots and blow-up mattresses fill the basement of a church that now provides crucial services to people recently released from detention. Thousands of individuals and families were released from detention on the border by Customs & Border Patrol, most of them with GPS ankle monitors. Upon release, none of them were provided with assistance from CBP or ICE. Nearly all will travel to other parts of the US where they will then go through the legal process of having their asylum claims heard by the immigration courts.

(Top left) After being released from detention, a group of men, women and children from Guatemala wait to make phone calls to family at a shelter in Tucson, Arizona. (Top right) A young child recently released from detention plays with toys. (Lower left) Two women from Guatemala & Honduras wash dishes in the shelter Casa Alitas in Tucson, AZ. Both women had recently released from detention with GPS ankle monitors and were preparing to travel to family in other places across the US while their asylum claims were in process. (Lower right) Two young boys relax on a couch and watch TV after having recently been released from immigration detention with their mothers.

Two youth sit and watch a cartoon at the INN Project in Tucson, AZ. The two were released from detention with their parents.

A young woman from the Community Immigrant Youth Justice Initiative Alliance stands with dozens of members from the community at a Coming Out of the Shadows demonstration to demand the end of ICE operations in Kern County, CA and the release of those being detained in the Mesa Verde ICE Detention Center in Bakersfield, California. (March 23, 2018)

“Going to the detention center was really difficult. Her appearance had changed drastically. Her long, beautiful, jet black hair was gray. Her chubby cheeks were reduced to bone. Her beautiful smooth face was filled with wrinkles.

“This is something that continues to affect our community. Systematic racism continues to infiltrate our government, our schools, our jobs and our communities. Today, I ask all of you to no longer remain silent against this oppression. Because, we do matter! Our lives matter!”

Tania, youth organizer with the Community Immigrant Youth Justice Initiative Alliance

In the desert outside the Adelanto ICE Processing Center on Good Friday in 2018, parishioners follow representatives of the Catholic Diocese of San Bernardino in protest of immigration detention practices and in solidarity with those men and women detained inside. The group re-enact the ‘Stations of the Cross’. They reflect and pray to Jose’s Way of the Cross - Viacrucis de Jose, an adaptation by Anton Flores-Maisonet of The Way of The Cross of the Migrant Jesus by Gioacchino Camprese, CS.

On July 19, 2017, a group of 15 young women in quinceañera dresses stand together on the steps of the Texas State Capitol in Austin, TX protesting the new immigration enforcement law, Senate Bill 4. The Bill was signed into law on May 7, 2017 by Texas Governor Greg Abbott. The law bans sanctuary cities in Texas and requires local law enforcement to cooperate with federal immigration officials, such as permitting local law enforcement officers to request proof of legal residency during any routine detention, such as a routine traffic stop.

“We are here to take a stand against Senate Bill 4, the most discriminatory and hateful law in recent history! SB4 is not only an attack on immigrant communities. It threatens the lives of all people of color.

“No matter if your family has been here since before or if you immigrated here recently…

“…this law creates fear and distrust in our communities and it will tear families apart!”

Magdalena Juarez, 17

An image of President Donald J. Trump is projected onto the border wall in Nogales, AZ. Students from local high schools contributed art to the ‘Borderlands’ project which was presented as an evening projection against the border wall.

A bus contracted by ICE carries over 30 detained immigrants of various nationalities into the Yakima Airport in Yakima, WA. They will board a chartered flight and be deported from the US.

Chains are removed from detainees and placed on the pavement outside of an ICE bus after detainees were released and deported to Mexico in Nogales, Arizona.

An empty plastic bag issued by US Customs and Border Protection to hold personal belongings during detention or while transferred or en route to deportation. The bag belonged to a man who was deported to Mexico.

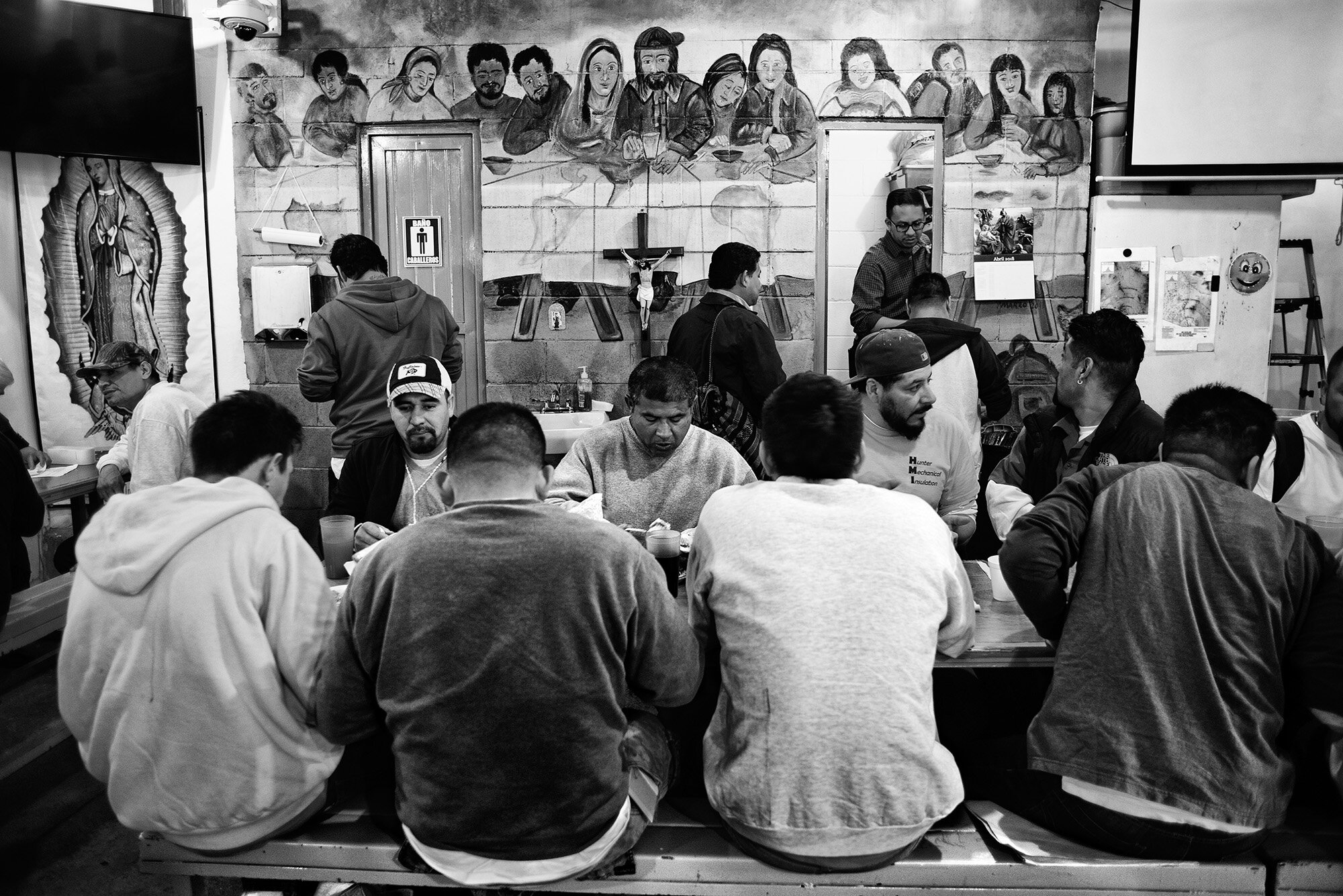

Less than an hour after being deported to Mexico by ICE, almost 100 men and women gather at the Comedor in Nogales, Sonora. Run by the KINO Border Initiative, the center provides assistance to those recently released from detention and deported. (2018)

This 44-yr-old man was arrested by ICE while walking down this section of sidewalk in Phoenix to a bus stop that would take him to work. He spent one year in detention, then was deported.

“ICE picked me up while I was walking down a sidewalk to the bus station. I was going to work. All of a sudden 8-10 US Marshals in different types of cars and a van surround me on the sidewalk. I’ve done nothing. I was in the process of appealing my case and I had fifteen days left. I said to him, I have 15 more days, why are you arresting me? The US Marshal said to me, I was looking for you.

“I didn’t do anything bad. I can’t understand it. In detention the lawyers were helping me and everything was going right. I was there for a year. Then in the middle of the night, they woke about twenty-five of us up and said, You’re going home. You’ve got to be happy. There was a paper you had to sign for your release. I asked to read it. They said, No. Do you want to go home or stay in detention? So, I signed it. Everyone walked in a single-file line. I was the last one. Everyone walked onto the bus. At the last minute, they turned me to walk in a different direction. They put me in a cold room and I was there for 24 hours. Then they took to me to different place with about seventy other people and we waited. They handcuffed all of us and our feet too and said we were being deported.

“I can’t make my life here. My life is with my family. Over here I can’t live. They changed my life so fast. I don’t believe anymore. I’m so alone right now. I gave up on God. In 3 ½ hours, my life changed so fast.”

44-yr-old asylum seeker. Detained for one year. Deported to Mexico.

39-yr-old Salvador was brought from Mexico to the US by his parents when he was two years old. He has spent his entire life in the US. Initially pulled over in a traffic violation in Utah, he was arrested, then ICE put a hold on him. He was in detention for over six months before being deported to Mexico.

"I was transferred 7 different times through 5 different cities - three buses, two planes, a van then more buses. My hands were cuffed with a chain around my waist like this for the entire time. After several days, they finally dumped me off at the border and deported me here to Mexico."

“I lived in US for 30 years. I have three children who are all US citizens. [In detention] I ended up on suicide watch because I had such anxiety and depression. My body gave up. I had a 103 fever and I was on the floor and I thought, I want to give up. I was detained for one year. I thought, If I don’t get out of there I’m going to die. I have a good family and they would say, When are you come back home? I would say, I’m being deported. I can’t come home.

“You sink into a hole and that is it. Americans have no clue about what is going on. They don’t see it.”

Rodolfo (55) lived in the US for 30 years. Detained for one year. After being deported, he sits in the courtyard of a migrant shelter in Tijuana.

“It was a small flight. There were eight people on the flight. There were a bunch of people being sent back to Mali and some of us to Mauritania. We were chained up the whole time. The trip was like 15-18 hours and we were chained up the whole time.

“I was just trying to be strong. But I was saying, Life is over now. I just don’t know. What’s next? How am I going to see my family again? How am I going to survive? There was another guy on the plane and he was crying too.

“But, I fought though. I fought. I put my money in it. They tried to mentally destroy me. But I did what I told them I was going to do. They’re going to have to put chains on me and deport me. I was ready to be in detention for 2-3-4 years just to fight to be with my family. I’m a strong person. I’m strong minded too. But it’s just how it was.

Asylum seeker from Mauritania who had lived in the US for 14 years. His American-born wife and 2 children are US citizens. He was detained for 5 months then deported to Mauritania.

Moments after departure, a Swift Air flight chartered by ICE carries detained immigrants from the Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport in Mesa, Arizona to San Diego and beyond. (January 12, 2019)