“At night I would lie in my bed and just think. Being in detention kills you psychologically.

“I had to make myself think like I wasn’t in detention. I did this so my mind wouldn’t betray me.”

An asylum seeker from Honduras.

Mexico

24-yr-old Wilson left El Salvador because the violence and aggression from gangs now threatened his life. 35-yr-old Herman fled Nicaragua when he realized the government was looking for him after he participated in protests calling for the overthrow of President Daniel Ortega in 2018. 32-yr-old Cesar left Cuba in search of someplace where he could claim political asylum. 17-yr-old Abdoulaye had no choice but to leave Guinea because of government crackdowns from post-election violence in the African country. And overtaken with a paralyzing fear of being killed by her husband after years of domestic abuse, 34-yr-old Elvia (name changed) fled Honduras with her two young children.

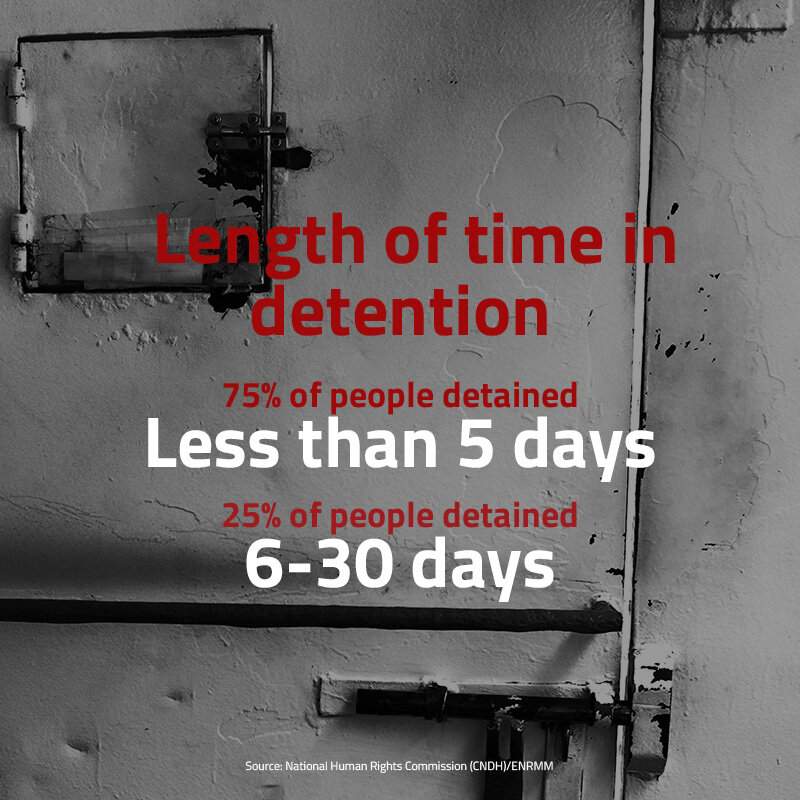

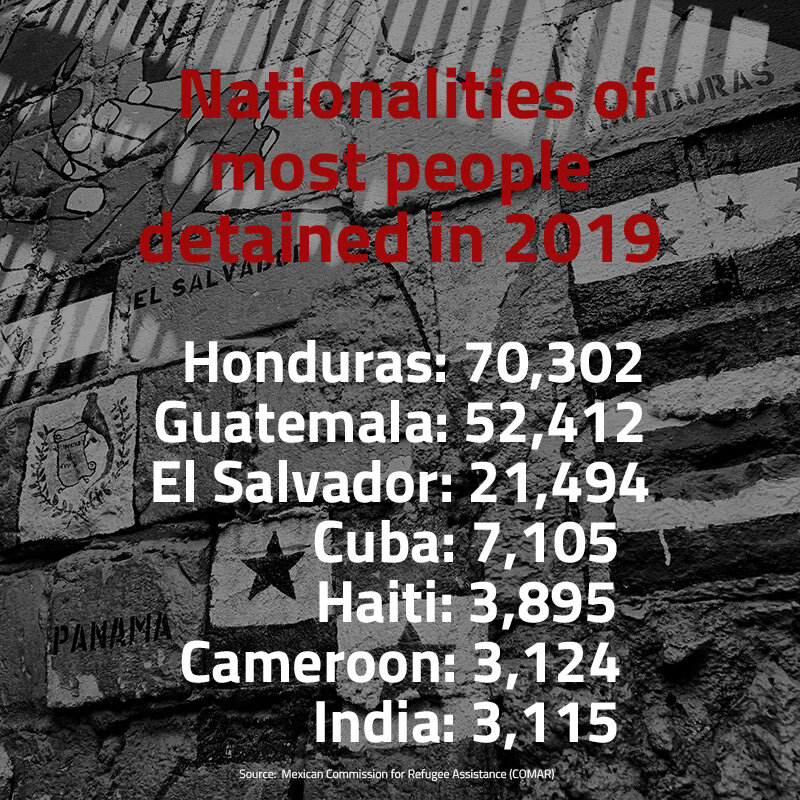

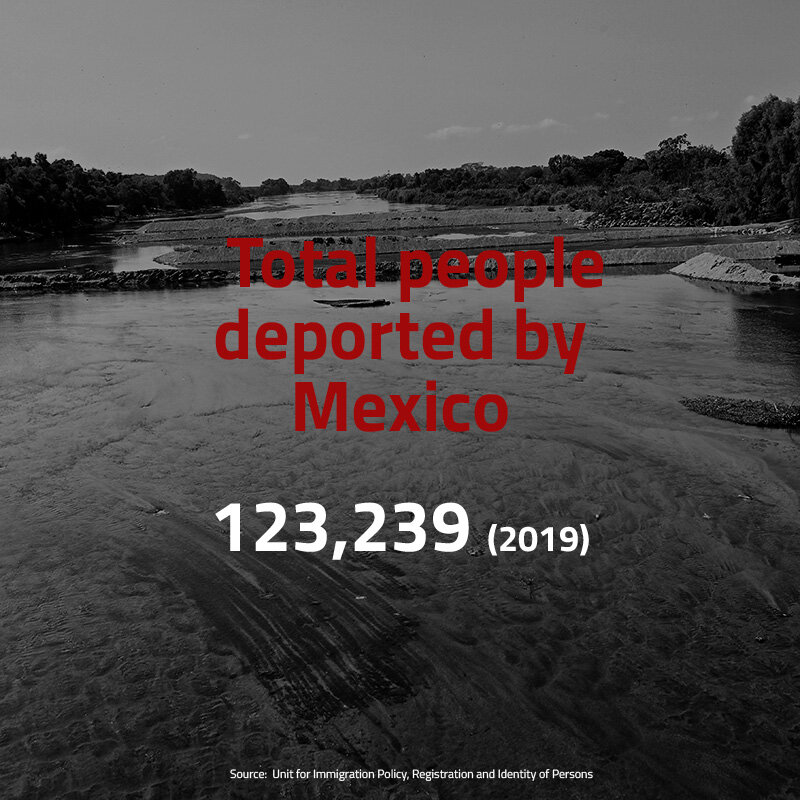

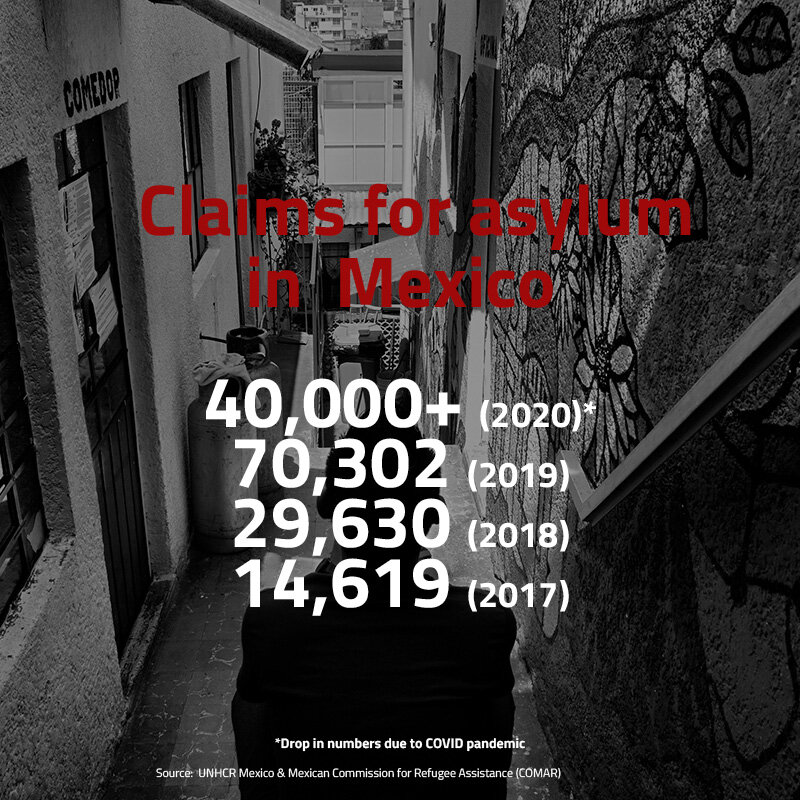

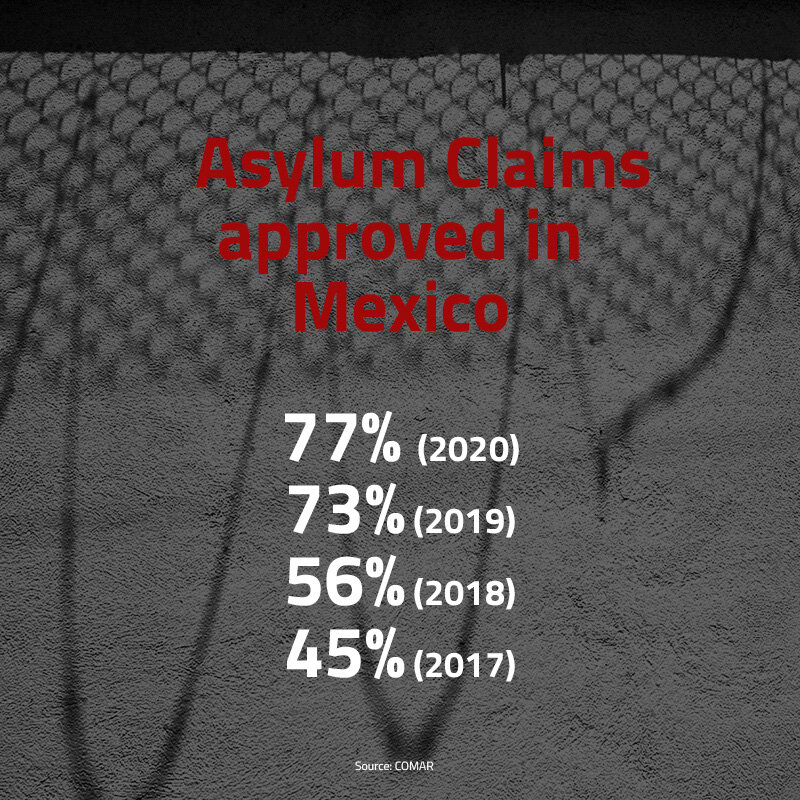

Similar stories are shared by tens of thousands of others who turn to Mexico for safety and sanctuary each year. While 92% of those migrants entering into Mexico in 2020 originated from Central America, individuals from over 90 different countries made their way to Mexico, either as a destination to claim asylum or as a transit point on a much longer journey to the United States. For those who turn to Mexico for asylum, many cross into Mexico and reach an office of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) where they apply for asylum. Yet, many find themselves experiencing an unforeseen trauma: immigration detention. While in detention, migrants can claim asylum and are often released to continue their process in freedom. In 2019, according to the UNHCR, close to 10,000 asylum seekers were released from Mexican immigration detention centers.

Policies for detaining immigrants in Mexico have existed since the late 1940s and have been enforced by a variety of government offices over this time including local authorities, state officials and federal offices and most recently (since the early 1990s) the Instituto Nacional de Migración/the National Institute of Migration (INM). For decades ‘Migratory Stations’ were mostly local jails and police stations but in the early 2000s, Mexico began to construct more formal detention centers.

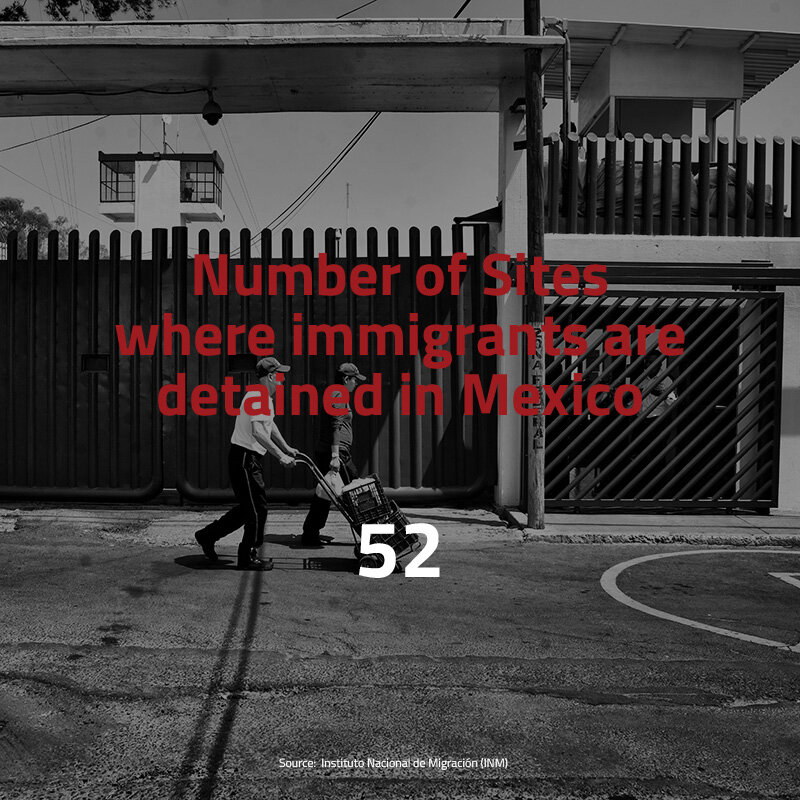

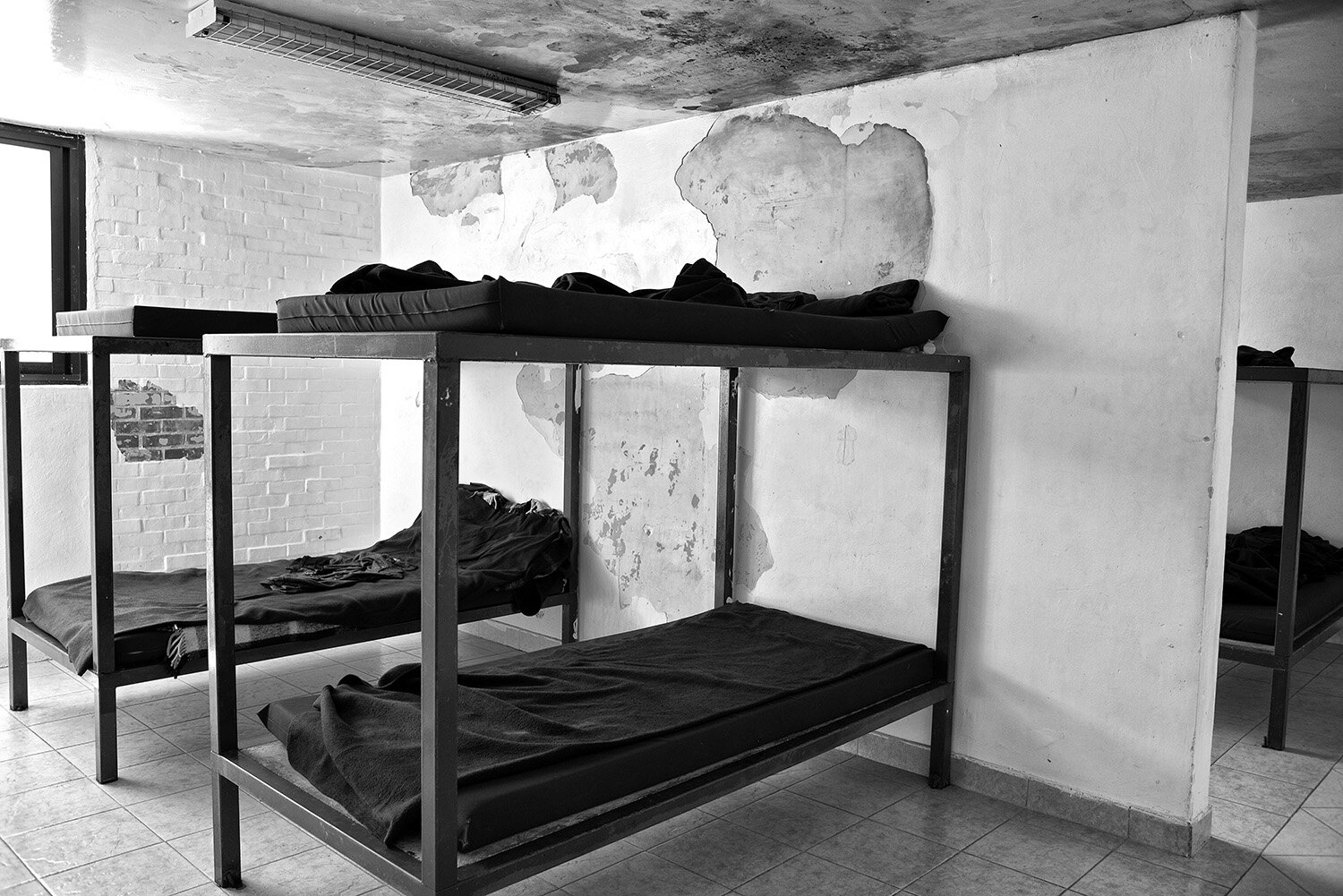

Mexico has over 50 sites where migrants are detained, including large detention centers in Chiapas, Mexico City and Veracruz that collectively can hold over 2,200 people per day. Prior to COVID, the number of people detained in Mexico increased each year from 2017-2019, reaching over 180,000 people detained in 2019. Overcrowding in detention centers is well documented and those who have experienced detention commonly share stories of unsanitary conditions, shortage of food and lack of healthcare.

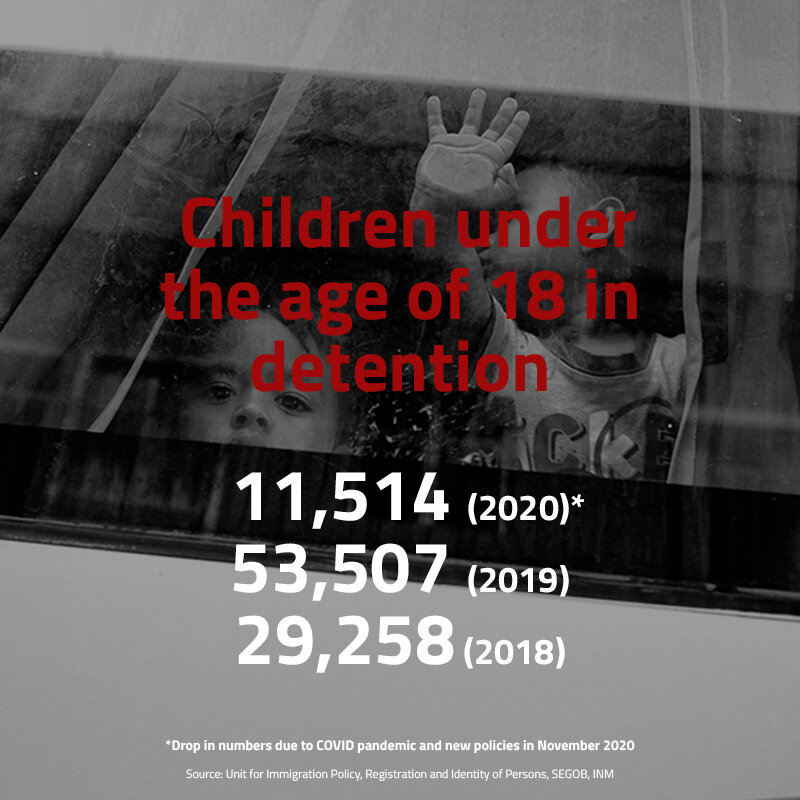

Civil society organizations in Mexico have spent years creating and launching alternative to detention programs as well as pressuring the government to change its policies. Until 2020, detention centers divided the population between men, women and families. Families were considered only women, girls and boys under the age of 12. From 2018 to 2019 the number of children detained who were under the age of 18 nearly doubled in size from 29,000 to 53,000. But in November of 2020, the Mexican government introduced legislative reform stopping the detention of children. After years of harsh immigration policies. this new legislation, which came into effect in January 2021, was an optimistic sign, although challenges remain in regards to the Mexican State having the capacity to provide appropriate care and attention to children and families in non-detention facilities.

Still, tens of thousands of people continue to be detained each year in Mexico. The impact detention has on them is both traumatizing and debilitating and discourages asylum seekers from claiming asylum, which puts them at risk of deportation back to the countries they fled from.

Estación Migratoria Siglo XXI or Tapachula Migrant Detention Center is located in the southern city of Tapachula in Chiapas.

People move back and forth over the border between Mexico and Guatemala using rafts across the Suchiate River.

Estación Migratoria Siglo XXI or Tapachula Migrant Detention Center is located in the southern city of Tapachula in Chiapas. It is the largest immigration detention center in Mexico as well as Latin America. Built in 2005, it can hold a capacity of up to 960 people but often holds more. African migrants from Guinea, Sierra Leone and Democratic Republic of Congo who had fled war, political violence and human rights abuse wait outside the detention center in Tapachula. They wait for permission to travel north to the US border. Most will be detained in Mexico before being permitted to continue their journey.

A 27-yr-old asylum seeker from El Salvador spent 13 years living undocumented in the United States. While living in California, he worked, started a family and had a daughter, who is a US citizen. In 2015, he was arrested and then spent 1 year and 4 months in immigration detention while he fought his deportation from the US. In 2017, the United States deported him back to El Salvador. Unable to live in El Salvador, he arrived in Mexico in January 2019 with a large caravan of over 13,000 other migrants. He was arrested by Mexican Immigration and detained. After 39 days in detention, he was released to a shelter while his asylum case is considered by Mexican authorities.

“I spent 39 days in detention in Mexico City. It’s not that much compared to the time I spent in detention in the United States, but the danger here is different. Those 39 days felt much longer.

“Half of my time in detention here was spent trying to mentally survive. The problem is you don’t know what kind of people are going to be in detention with you. Some, like me, are there to fight their asylum case so they can stay in Mexico. Others don’t care. They are just passing through on their way to be deported.

“Now, I have to start from scratch. I can’t go back to the US for 5 years. If I go back to my country, you never know what will happen to you when you get off the plane.”

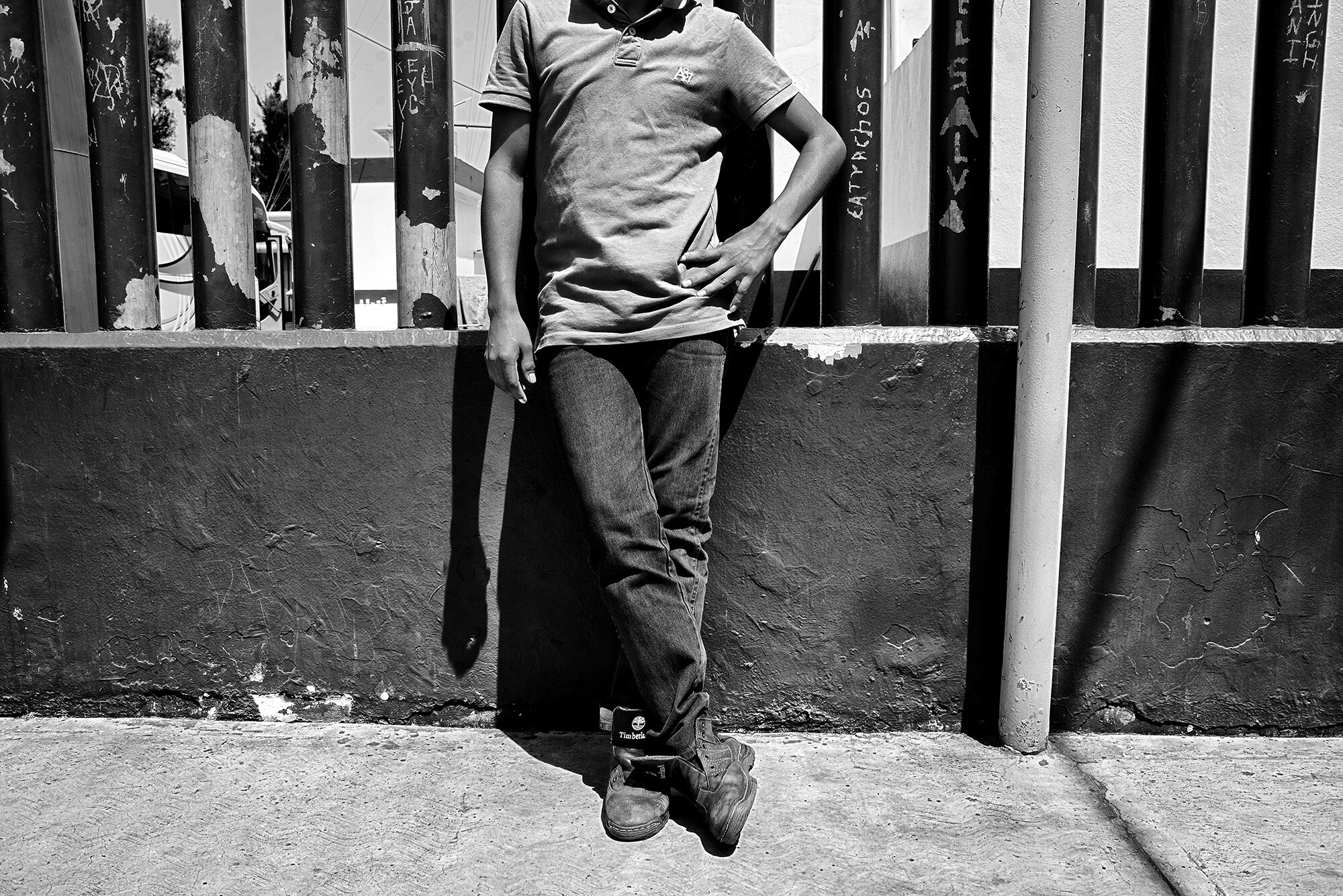

This 26-yr-old asylum seeker from Honduras arrived in Mexico in late January 2019. He was arrested by Mexican Immigration and then spent 18 days in immigration detention. With assistance from civil society groups, he now rents a small room in an apartment while he waits for his asylum claim to be processed

“The situation is really bad in my country. There are no jobs and the gangs are everywhere. I came to Mexico to claim asylum. While in immigration detention, they tried to have me sign my own deportation and I told them, ‘No’. I told them I wanted to stay here and have a better life. They tried to have me sign my deportation three different times, but each time I refused. I had to fight to stay here in Mexico.

“It’s a nightmare in detention. The pressure to go back to your home country is enormous. That’s what they want you to do.”

After fleeing his home in the Democratic Republic of Congo, this 30-yr-old spent over a year migrating through Europe and South America before arriving in Mexico City. Upon arrival at the Mexico City airport, he was put in immigration detention for 27-days. He now lives in a shelter while he waits for a decision on his asylum claim.

“I arrived in the detention center late at night. I walked though the door and I saw all of these officers standing inside. I thought it was a jail. The next morning, I felt like I was in a jail for the first time. I met a guy from Somalia and I asked him, ‘Is this a prison?’ He said, ‘It’s not a jail. It’s a detention center for migrants’. What he told me did not convince me.

“I asked one of the officers, Is this a prison? She said, It’s something similar, but it’s not a prison. I asked, What do they do here? She said it was a place where they normally deport people and check their documents. It was at that moment when I knew they had all control over me.”

“Living with liberty is much better than living life without liberty. You may have no money but it is better to be free. I couldn’t enjoy life, yet I was in detention.”

A 24-yr-old from El Salvador, looks at his mobile phone on his bunk at a community shelter for migrants in Mexico City. He spent 103 days in immigration detention. As an alternative to his detention, he was released to a community shelter.

“There is a lot of racism in detention. They discriminate against you because you are from Central America. They think that all of us who come from Honduras and El Salvador belong to gangs but we don’t. We’re not leaving our home country because we want to. We’re being forced to leave. I’m not happy that I had to leave my family and be away from them, but it is a decision I had to take.

“My case is still in process. I was worried I would have to stay in detention for the whole time my asylum claim was being processed. But I’m here now and after everything I’ve been through, I am more hopeful.”

After his life was threatened by gangs and his father was killed, this 24-year-old man from Honduras fled to Mexico for asylum with his wife and children. He was detained for 12 days. While in detention, he was separated from his family. The health of his children worsened while in detention and as a result, his wife became desperate and agreed to be deported back to Honduras. Here he sits in a room he is renting in the city of Tapachula as a neighbor’s child plays in the apartment block.

“The health of my children got worse while in the immigration center because they could not see a proper doctor. My wife signed her deportation and was then sent back to Honduras with my children.

“I never imagined going to the detention center. We were taken to the detention center together in a bus. They told us we would be separated. We arrived. I got off the bus and they took my wife and children to another place in the detention center. I didn’t say goodbye to her or my children because I never imagined they would actually separate us the way they did at the detention center.

“There is a sign in the detention center that tells you about your rights. It’s a list of rights. I went to security and I told them that I need to see my wife who is on the other side. The the guy said, “You can’t if your wife doesn’t request to see you.” I know both of us requested to see each other, but they didn’t permit let us to see each other.

“After seven days, I received a request for a visit. I was happy because I thought I would see them. But it wasn’t them. It was a relative. She called to tell me that my wife and kids were deported. That’s how I found out. That’s where she is now, back in Honduras.

“I got off the bus in the detention center and I haven’t seen them since.”

(Top Left) Estación Migratoria Las Agujas in Mexico City (Top Right) Names are etched into the metal bars of a wall at the Estación Migratoria Las Agujas in Mexico City. (Lower Left) Young men hang out and kick a ball around in a courtyard inside the Mexico City detention center. (Lower Right) A young man from Honduras in the Mexico City detention center.

“In detention you never get answers. You never receive notification about your case. You felt neglected, like everything was over.

“I saw other asylum seekers and they were in detention for only 15 days or so. I actually got to the point where I was ready to self deport. But I didn’t.”

Asylum seeker from El Salvador. Detained in Estación Migratoria Las Agujas in Mexico City for 4 months.

A child plays on a toy while he and his family are detained in the Estación Migratoria Las Agujas in Mexico City. In 2019, over 53,000 children under the age of 18 were detained in Mexico. In November 2020, Mexico changed its legislation to stop holding children in detention.

(Top Left) Two young men from India sit on a top bunk in one of the dormitories inside Estación Migratoria Las Agujas in Mexico City. (Top Right) Racks hold backpacks, luggage and personal belongings of people detained. The racks are organized by nationality. (Lower Left) After one day on an immigration bus, over 40 men arrive at the Mexico City detention center. The men were being transferred from a detention center in Hermosillo, Sonora. Each week up to 10 buses transfer detainees from Mexico City to the southern city of Tapachula for deportation. (Lower Right) Men line up in a basketball court in Estación Migratoria Las Agujas in Mexico City.

A detained migrant from Colombia hugs his girlfriend in a visitor area inside the detention center.

Detained inside the Mexico City immigration detention center, a group of women with their children congregate underneath a tree to escape the hot afternoon sun.

A bus for women and families and a separate bus for men transport asylum seekers from the Estación Migratoria Siglo XXI or Tapachula Migrant Detention Center located in the southern city of Tapachula to a network of community shelters. (Left) Tania (25) and her two young sons (2 & 3) from Honduras were detained for 18 days before being released. (Right) Having fled from Honduras, these three young men (ages 18-21) were detained for 17 days before being released.

A group of asylum seekers from Cuba rest in Albergue Jesús el Buen Pastor del Pobre y el Migrante or the Shelter of Jesus the Good Shepherd for the Poor and Migrant located in the southern city of Tapachula. Most plan to travel to the United States where they want to claim asylum. Not knowing what they will encounter as they travel north to the US border, they hope not to be detained in Mexico. In 2019, over 7,100 Cubans spent time in Mexico’s immigration detention centers.

“When you leave your country you always ask God that good things happen to you on your journey.”

24-year-old asylum seeker from El Salvador

With over 180,000 migrants being detained in Mexico in 2019, civil society groups and international organizations have pressured the Mexican authorities to see the benefit of a variety of Alternative To Detention initiatives. Once released from detention centers asylum seekers are provided with short-term housing in hotels and migrant shelters. Organizations are then better suited to monitor and assist them during the legal progress, and asylum seekers are in a better position to secure housing, safety and security as they wait for decisions to their asylum claims.

(1) Albergue Belén migrant shelter in Tapachula. (2) Casa Tochan shelter in Mexico City. (3) Asylum seekers shelter in Tapachula. (4) CAFEMIN shelter in Mexico City. (5) Albergue Belén migrant shelter in Tapachula. (6) Asylum seekers shelter in Tapachula.

Just released from detention, asylum seekers from Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Cuba wait to have conversations with staff from the UNHCR at a shelter in Tapachula.

“We don’t know how long it will take to get asylum, but that is OK. Our problem was not having to wait. Our problem was the conditions we were in while having to wait. We can wait as long as it takes.”

Carlos, 38-year-old asylum seeker from El Salvador. Family separated and detained for 8 months.

38-year-old Carlos and his wife fled El Salvador with their seven year old child in mid-2018. They traveled through Mexico with the intention of claiming asylum in the United States. They made it all the way to the northeastern border with the US before being arrested by Mexican immigration. The family was separated. Carlos was placed into a detention center, while his wife and daughter were detained in a shelter for families. They were separated and detained for 8 months before being released to a shelter in Mexico City where they would live as their asylum claim was processed.

“We thought we would be detained one month or so but never through we would spend so much time there. We were so afraid they were going to send us back to our country. That’s what we were worried about the most when we were in detention. We thought we were going to be sorted out soon, but in the end it took much more time. They said 45 days was the maximum amount of time we should be be detained but it was a lie.

“My wife was put in one place with our child. I stayed in a room sometimes with 100 other people. We’ve never been apart. I would tell them that I want to see my family. To see them I had to ask all of the time. They never tried to arrange for me to see them.

“My daughter doesn’t need anything else but to be next to me and her. That‘s all she needs. When you are little, I always wanted my parents. I always want to be next to them. That’s what we want. My daughter has felt this process even more than me. She is little. I am able to understand what going on but not her. She doesn’t understand.”

Tania (41) and her 18-yr-old son fled Honduras. They stand in the doorway of a small room they are renting as they wait for their asylum claims to be processed. The family of four arrived in Mexico and then spent 18 days in immigration detention.

“It was a terrible experience,” the son describes. “I have never been in detention in my life.”

“I had never committed a crime, but it was like being in a prison. While in detention, we were separated. I spent much of my time during those 18 days worrying about my mother and younger brother and sister because they were in a different section of the detention center.

“For me, there were so many different kinds of people in the detention center, including criminals. I tried to keep to myself and just make it through the time, but I had no idea how long we would be in there.”

Threatened by gangs and unable to pay extortion money, this 58-year-old woman from Honduras and her 16-yr-old son fled to Guatemala and then Mexico. In Mexico, they were detained for 19 days. While in detention, they were separated. When released, they temporarily lived in a migrant shelter and hope to reunite with family elsewhere in the country.

“I used to sell many things to make money, but where we lived, there were a lot of people with tattoos. The gangs asked how old my son was and they said, ‘Don’t leave him along because he is the perfect age to be part of a gang’. We were afraid and we moved and while I was working, the gangs wanted extortion money. I couldn’t make money so I sold everything to pay them off. Then the gangs took my house from me.

“I tried to apply for a humanitarian visa in Guatemala but they stopped the process. I thought, ‘Lord what am I going to do? I don’t want to go back’. So, I came to Mexico. We were stopped by immigration and I didn’t know what to do. They took my son to another place. We’ve never been separated. I didn’t know what would happen in detention.

“There was so much noise. Babies crying. Men screaming. I couldn’t sleep. I told the people there, ‘I don’t want to go back to my country. I need help. I don’t have anything. I don’t have a home’.

“My son turned 16-years-old when we were in detention and I couldn’t be with him. I was desperate to see him. I couldn’t even hug him on his 16th birthday.

“When we were released and came here, I couldn’t sleep for almost a week because it is so quiet here. I became used to all the noise in the detention center.”

Jose, a 24-yr-old, fled gang violence in his home in El Salvador. He arrived in Mexico with the caravan in October 2018, but was arrested and detained by Mexican immigration in the town of Mexicali in early 2019.

“In Mexicali, immigration raided the house where I was staying. There were 15 people with me in the house. All but three were arrested and put in detention.

“The first thing that came to my mind when I entered detention was that they were going to deport me. It made me very sad because it had been such a difficult trip. I spent 39 days in detention. Now that I am out of detention, life is much better. But right now, I am just waiting.”

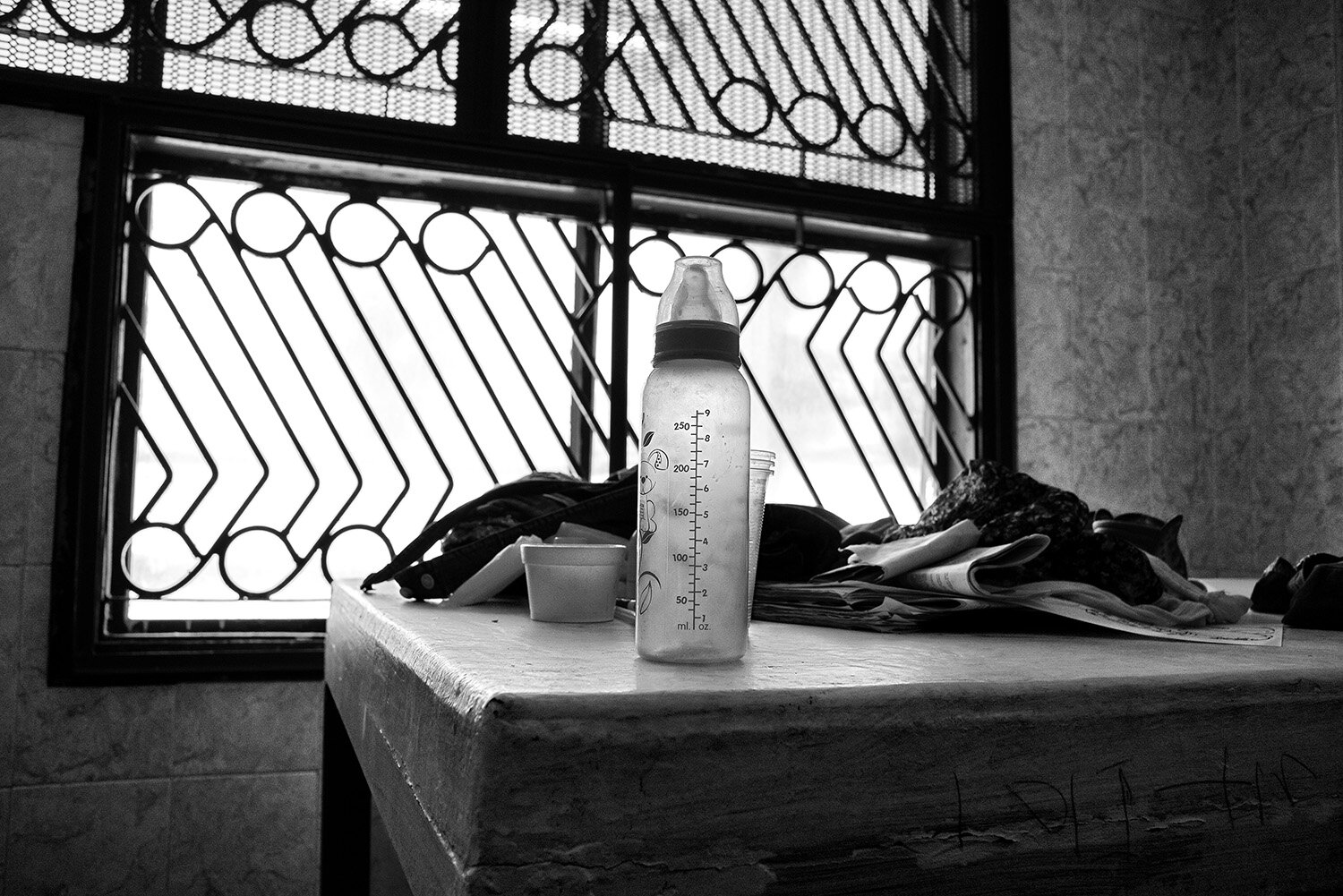

After suffering domestic violence, this 20-year-old woman from Honduras fled to Mexico with her 2-year old son. Together they spent 10 days in detention. She is a recognized refugee by Mexican authorities. Upon her release from detention and with the assistance of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) she temporarily lives in a shelter for migrants and others released from detention.

“I had no idea I would be detained. I crossed the river, but immigration stopped me at a highway checkpoint near San Cristóbal de las Casas. They took us in a van like a dog cage and we stayed with immigration for 2 days in Tuxtla. Then they transferred us to the detention center in Tapachula where we spent ten days. They asked me to sign a paper to agree to my deportation but I refused.

“In detention my son didn’t eat much and had diarrhea because of the food. They only gave us 2 diapers for the whole day. We’d requested more diapers but the guards would say, ‘Why didn’t you bring some diapers yourself?’

“When I was released, I signed the papers and I asked them, ‘Where do I go? I have no where to go now. I have no personal belongings. I have no money.’

They said, ‘That’s not our problem.’

There are so many women in detention who want to get out. The women leave their homes because of gangs or domestic violence. We shared our histories with each other inside. One of the ladies was also from Honduras. Her 9-year-old son was killed by gangs. She ran a small business but had to pay extortion money to the gangs. When she couldn’t keep paying, they killed her son. She had to run because they were looking for her.