"When you hear the doors, you feel like you have lost yourself. You have no voice. You are invisible.

"The essence of being human, it feels like you have lost this."

United States

AMERican Gulag, Part 1

"Loss of freedom, constantly being monitored, being separated from family, friends and the outside world and not knowing if you will be released or being deported back to your country…that feeling is the story of my time in prison the United States Prison.”

These were some of the last sentences from a hand-written letter, postmarked October 9, 2018. The letter was sent from inside the Northeast Ohio Correctional Center in Youngstown, Ohio in response to a letter I had written several weeks earlier. We had never met face-to-face. We had never shaken hands in a gesture of saying Nice to meet you or Hello or Goodbye or Take care of yourself . This gentleman had travelled halfway around the world to seek sanctuary in the United States. He had travelled through fourteen different countries, more than most people born in the United States would ever visit in an entire lifetime. His penmanship was elegant. His words and his voice were articulate and genuine. The word prison was scribbled out in his original sentence. As I read it then and read it again now…I can feel his pause when he lifted his pen off the page after writing the letter s in States. Do I put a period here? I imagine him thinking. No. Then he scribbled out the word and wrote it at the end of the sentence to more accurately reflect his experience and the place where he had put so much faith for his future.

When we exchanged these letters, he had already been in ICE custody for over two years. He had not broken a law. He had presented himself to officials at an official point of entry on the US/Mexico border. He did not know the US Government would put him in shackles, then transport and incarcerate him somewhere in the United States, out of sight from the American public. He did not know the US Government would remove him from the world. He had vanished into the US Immigration Detention system, left to languish in an ‘administrative hold’ while waiting deportation or while waiting for answers related to his asylum case as it crawled through the immigration courts. His is just one story, yet hundreds of thousands of others like him possess the same unfortunate and traumatic experience.

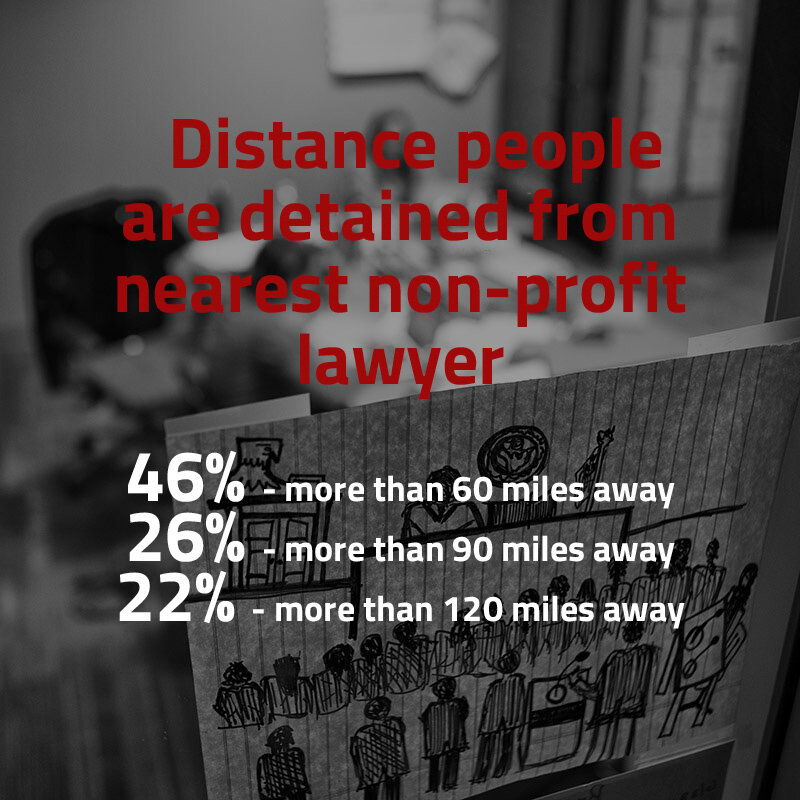

The US has the largest immigration detention system in the world. Constructed intentionally to be out of sight from the American public, difficult to reach for families to visit and for lawyers to access, places like Eloy, Otero, NWDC, Sierra Blanca, Adelanto and Prairieland are buried in the nothingness of a remote desert or farmland or in the middle of an industrial area. The isolated, desolate location of these immigration detention centers is representative of the strategy ICE and DHS has taken to do everything possible to isolate and dehumanize all of those who are being held inside them. They are also representative of the entangled relationship between political interest and power and profit-driven corporate America.

Does the US public know that scattered across the landscape of the country exists an American Gulag system? I imagine they don’t. The visual translation of this extensive web of immigration detention prisons usually comes in the form of graphic maps and info-graphics, leaving most with an abstract and intangible picture that is left merely to the imagination to then construct what the scope and scale of this system actually looks like. Five years ago, I set out to see what this American Gulag system looked like. And more importantly, to hear the stories of those whose lives have been impacted, damaged or in some cases, destroyed, by the ever-expanding use of immigration detention in the United States.

It’s been over five years now, nearly 40,000 miles of interstates, highways and country roads and over 150 hours of interviews and conversations with some of the most resilient and inspiring people I have ever met, many of whom are found in the three chapters of this project dedicated to the United States. Yet, even as this system has started to take on an unimaginable shape in its enormity, I still feel disoriented and lost and I’ve come to realize it is much more sinister than I ever could have imagined.

THE NUMBERS

56,816 people/day

detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2025 in detention centers dedicated to ICE. Most are owned and operated by corporate prison companies.

Since 2018, the project Seven Doors has documented 36 detention centers and 3 migrant children’s shelters across the US, primarily located along the west coast and southern border states.

*as per ICE on 7/13/2025

THE STORIES

ELOY DETENTION CENTER

ELOY, ARIZONA

“I never knew when I would be released. I spent twenty months there. That was the biggest challenge. Not knowing. And then inside you have all the rules in that place. There were so many rules. I came out traumatized.”

Martha, asylum seeker from Honduras

Detained for 1 year and 8 months

“I thought I would only be in for a month. Then it turned into 4 to 6 months. Then 2 years and four days. None of the women in detention have the benefit of the doubt. Nobody believes them. All you see is confinement. The detention center is where they get away with all of this. There is no accountability and no transparency for anyone, because it is a private prison. The women slowly become invisible.

“When we talk about detention centers, you better believe there are at least 10 corporations, private companies, profiting off of the bodies that are being detained there.

“Peoples’ human status is up for question there. Their ‘human-ness’ is up for debate. These places are everywhere and they want to build more.”

Alejandra

Detained for 2 years and 4 days

“It’s truly a prison. It’s not not a prison. The people inside are trying to make sense of it all and they have spiritual needs to be able to do this.

“I think to myself, I live and participate in a system that does this?

“And we won’t change it. This is the system and the people inside carry the sorrow of being failed. Personally I can’t help but feel outraged. I tell them, If you want me to, I will visit you until you leave this place.”

Volunteer Visitor

LA PALMA CORRECTIONAL CENTER

ELOY, ARIZONA

“Never in my life have I had to stand in front of a judge. Never have I had to be in court before. Here…it was terrifying standing there by myself.

“The ICE attorney, she made me feel confused. The atmosphere in the court was freezing cold. I lost my voice because it was so cold and the judge yelled at me. She ordered me to, Talk louder! The judge and ICE attorney would talk and discuss things and I had no idea what they were talking about. I never knew what was going to happen. At the time, I felt like the whole world was above my head. I want to be done with all of this. I don’t want to go through all the stress anymore.

“I didn’t want to break the law. I didn’t want to start my life in the United States by doing something illegal. But by NOT doing something illegal, made me ineligible for bond and now I’m in here. It doesn’t make any sense. But it is the law and the law is blind.”

Lee, 25-yr-old asylum seeker (undisclosed country)

Detained for over 1 year

FLORENCE CORRECTIONAL CENTER

Florence, Arizona

“I stayed in Florence for one year. It was the worst experience of my life. I saw people die in Florence. One man had a heart attack. I’m sure it was from the stress. Another man, his face swelled up. ICE did nothing to help the guy. I said, Hey! Help this guy! They did nothing.”

Carlos, 44-yr-old asylum seeker from Mexico

“I left Honduras because of the gang violence and also because I am a transgender woman. As soon as I entered Florence, everybody started making fun of me. They started yelling out stuff. They would call me insulting names. They harassed me at night as I was lying there and wouldn’t let me sleep.

“At the beginning, they made me take a shower with all the other men at the same time. They would start staring at me and some would masturbate in front of me. So, I had to stop going to the showers. Instead of going to the shower, I started cleaning myself in my cell while everyone else was showering. For the first six months, I shared a cell with only one other person. Our cell had a small sink so I would use it to clean myself instead of showering with all the other men. People started noticing that I was missing from the shower, so they told the officers I was cleaning myself in my cell, which wasn’t permitted. The officers came to my cell, grabbed me and took me to the ‘tank manager’. After six months, I was moved into a cell with 16 other men. It was horrible. I didn’t know what was going to happen. Every day, it was something, and I was so afraid. I didn’t feel like going on. I felt like I couldn’t make it any more.

“Out of two hundred people in my tank, there were only two other transgender women. Only three of us out of two hundred. Me and two others. There was a group of detainees that were very Christian and religious. They would say, You’re an aberration! You’re a disgrace! You’re never going to make it to heaven! You’re a sin! They were really rough with us. The officers would not do anything to stop it. It was so frustrating. We wouldn’t dare say anything to the officers because if we said anything, the officers wouldn’t like it and they would send us to the hole. It’s a place where I wouldn’t’ want to be.

“Toward the end was the worst. My level of fear was so high. I wouldn’t want to get out of bed. I wouldn’t want to wake up. I didn’t want to keep on going because I didn’t want to be abused again. I expected something else when I came to the United States. I had other expectations. I thought that if I came to the United States, I would be safe and that there would be more understanding about transgender people or the LGBT community. But they didn’t have any respect for us. It was all so humiliating.”

Alejandra, 34-yr-old transgender woman asylum seeker from Honduras

Detained for 9 months

FLORENCE SERVICE PROCESSING CENTER

Florence, Arizona

“After those first days of being in detention, I was ready to self deport. It was a very lonely and isolated time. You feel totally disconnected from the world.

“The Mexican/American guards, they look at you as if they are better human beings than you. The Mexican/American guards were like this to all of us from Mexico or Central America. They would call us, Shit Hispanics. They would only speak in English to us. Never in Spanish. Speak English not Spanish!, they would say. And they knew I couldn’t speak English. We are in the US and we speak English here, they would say. They were always causing problems for us.

“In Florence you have all of these old people living in a trailer park right next door to the detention center. Do they come and visit? No. Why don’t they come and visit and find out what the truth is? There are a lot of people like me who if they didn’t come to the US, they would be dead. We came here for a life to live. Why do so many people here think we are not human beings?”

JC, 25-yr-old asylum seeker from Honduras

Detained for 7 months

“It was intimidating not having been to a prison before. I didn’t know what to expect. The chain link fencing with wires everywhere. The disembodied voice talking to you though the box at the entrance, and the gates opening and closing when you walk in, another door closing behind you and then waiting for another gate to open. I thought, What the hell have I gotten myself into?

“You push buttons for the door to open, then you push more buttons for other doors to open. You don’t actually sit with the person. You have to look at and sit across from each other with a thick pane of glass between you. You talk through a telephone. My first time, I felt a huge sense of relief that I could actually leave. And these guys are still in there and they don’t know when they are going to get out.

“The people I visit go through these emotional ups and downs. I can see them go from very happy to being absolutely depressed. I go to dampen the amplitude of these ups and downs.

“By being there on a consistent basis and talking with them about what is happening in the world, or in their previous life, its like I’m there temporarily creating a fantasy to release them from the reality of their circumstances.“

Rich

Volunteer Visitor

SAN LUIS REGIONAL DETENTION CENTER

San Luis, ARIZONA

“When they transferred me to San Luis, people inside said, So, you’re being deported? They said it was the place people go to before they are deported. It was terrible. I couldn’t go back home. Then I was transferred again…You sit and stare at four walls all the time and you’re not able to talk with people. Toward the end of my detention, I was so frustrated from everything. I couldn’t talk with anyone. If people tried to talk with me, I would get angry so I didn’t talk to anyone. There is nothing to distract you. Everything I had was circulating in my mind and there is nothing else. I would say to myself, I can’t do this. I can’t talk with people.

19-yr-old asylum seeker from Guatemala

Detained for 18 months in 5 different detention centers in

California, New York and Arizona

ADELANTO ICE PROCESSING CENTER

Adelanto, California

“When you hear the doors, you feel like you have lost yourself. You have no voice. You are invisible. The essence of being human...it feels like you have lost this.”

Rodolfo (55) Lived in the US for 30 years

Detained for one year, then deported to Mexico.

“We try to visit him as much as we can but that is usually once every few months. It is too far for us to travel and too expensive.

My youngest son misses his father so much. Three years, he’s been detained too long. We see him and he’s wearing the detention clothes. That’s not how I want my children to see him. But they need to see him. My son changes before and after he sees his father in the detention center. You can see his face change when he sees his father. He’s happy, but we have to leave and he’s still in there.”

Wife of man in detention

(He’s been detained for 3 years)

“When I walk into that room, through the metal doors that close behind you, there are often families visiting with a loved one who is in detention. But most inside don’t have someone to visit them. I look for the person who is standing all by themselves and I know that is the person I’ve come to meet. We talk and they share their story with me. That’s what I carry with me after our time together. I carry their story and that is one of the most important things I do. People don’t hear their stories or see them. But I do.

“Adelanto is built in the desert for a purpose: to make it hard for people to get to, for people to visit, for families to see their loved ones face to face.

“I go there to let people know there is someone who cares about them. To humanize their time there. I feel blessed to be able to meet people who have gone through so much in the places where they come from and then get here, only to be detained. I feel blessed to hear their stories and be a part of their journey. They need people. They need people mentally, emotionally and spiritually and they need people to give them some kind of hope because so much is done to make them lose hope.”

Eldaah

Visitation Program Volunteer

OTAY MESA DETENTION CENTER

San Diego, California

“The security guards are very racist there and they punish you for everything. The most difficult thing was not knowing when I would be released and the final decision for me to be let out was only one immigration judge.”

20-yr-old asylum seeker from El Salvador

Detained for 10 months

“We were discriminated against the entire time we were in detention. I’m a small woman. At first, they gave me small clothes to wear, but then to humiliate me, they gave ma extra large clothes. I couldn’t fit into them. They were just too big. They did things like this all the time specifically to humiliate and punish us. Psychologically it was very traumatic. During all of the nine months I was in detention, the guards refused to call me by my name. They always called me Sir or Mister.

“They always referred to me as a man and I actually faced more discrimination in detention than I did in my home country. But when you think of what life was like back home, you have no choice but to suffer through the detention.”

24-yr-old transgender woman seeking asylum from Honduras

Detained for 9 months

“You have no idea what detention looks like when you get there and you have no idea when you will get out. When I got moved from Border Patrol, you are in a van and you can’t see outside. All you know is that you are taken into a van. When that van door closed, you can’t see anything. I wanted to know where I was. When the van pulled up to the detention center, it pulled right up to the door. You saw some lights but you had no idea where you were. When you are there, you have no connection with the outside world. None. You just wait there and you see what they are going to do with you. Those seven months, it will never go from me.

32-yr-old asylum seeker from Belize

Detained for 7 months

IMPERIAL REGIONAL DETENTION CENTER

Calexico, California

“They put me in a blue uniform when I arrived. I met some guys who had been in detention for 2 years. Some for 3 years. I started crying for nothing. After eleven days they called me in for an interview. I told them, I don’t want to be here anymore. Right now I don’t know what I’m doing. The first month in, I was told that after six months, I would see a judge, but six months could turn into one year. I didn’t eat for three days. They put me in solitary. I said, Take me anywhere you want! I’m depressed and confused. Take me anywhere!

“I spent five months and crossed through eleven different countries to get to the United States. The journey through South America was terrible....and then to arrive in hell.

“In Somalia, I grew up by myself and saw a lot. I lived by myself and for most of my life I had freedom. I never thought I would be in prison. Seven months and no freedom.”

25-yr-old asylum seeker from Somalia

Detained for 7 months

“As a lawyer representing detained immigrants who have travelled through 11 countries to end up in a cold, sterile prison, it is heartbreaking.

Not only is Calexico far from any large city, it is located in a very desolate area. It is surrounded by miles of desert and agricultural fields. It is hot in the summer, and cold in the winter. This spatial reality reflects back to them the aloneness they feel in their soul. Apart from their families, apart from any legal help, apart from the court. They only see a judge by video. They are alone.

Many days I go in feeling tired and overwhelmed by the amount of people I have promised to see that day. Knowing for many of them I am their only chance to get asylum. They can suffer unimaginable torture, then travel through these 11 countries and risk their lives to come to this country that doesn't want them. They don't realize this until they are here watching our TV and hearing all of the horrible things being said about them and the countries they come from. But yet, they have hope, irrepressible faith, and trust in the goodness of America. I sorely lack that right now, and it renews my own faith in our immigration system. If they can have that determination after all that they have been through, I can go forward also to fight against a bad ICE decision or a weak credibility determination or a denial by a judge.”

Elizabeth

Immigration Attorney

ESTRELLA DEL NORTE (North Star)

Tucson, Arizona

Immigrant Children Shelter

Company: Southwest Key Program (Non-Profit status)

Capacity: 300 beds

NORTHWEST DETENTION CENTER

Tacoma, Washington

“You never get used to seeing the effects that detention have on your clients. I always get to leave at the end of the day.

“A certain amount of what we do is really focusing on what we can do for clients and knowing and supporting them through these hard times and decisions. And, at least for the time when we are in there with them, really making sure we are treating them as human beings and as people. There is so little of that in detention.

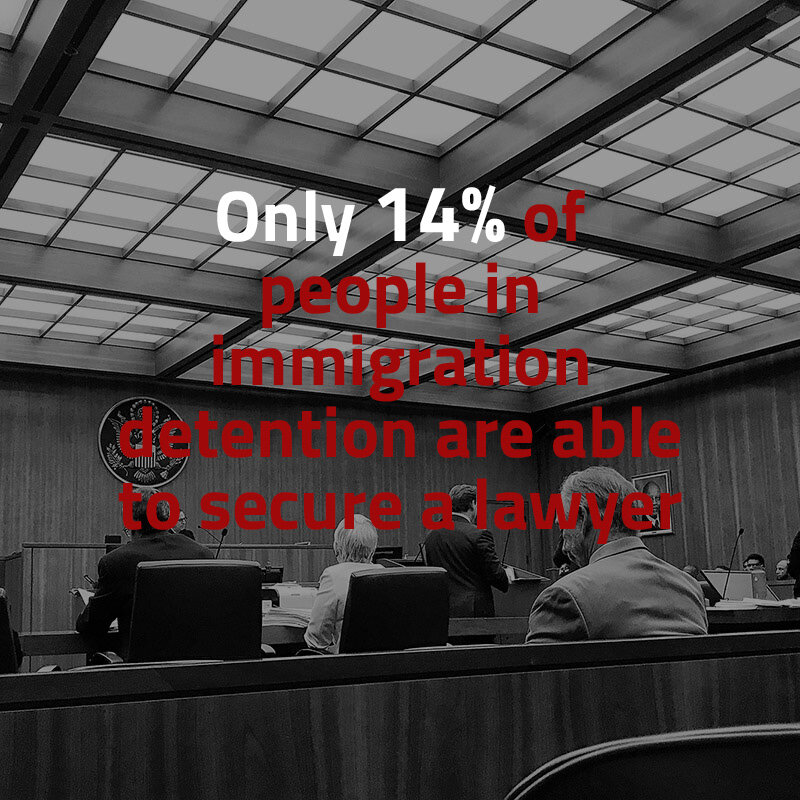

“I think how important an attorney is and how devastating detention can be for people in the process and their ability to have a fair hearing. People just don’t have a fair shake in the system. We know we don’t have the resources to represent everyone. That discomfort of knowing that there are people who we meet with who we are not going to be able to represent and knowing that a lawyer would have a significant impact on their case and having to say No and having to say No when you have the knowledge that it would make a difference, it’s a terrible part of the job.”

Tim Warden-Hertz

Immigration Attorney

“I was brought to the US when I was five years old. The US is pretty much the only thing I’ve known as far as home goes.

When I got to the ICE facility in Portland, there was around seven of us.

They got us all together, put us in a van and took us to Tacoma. It was the longest ride ever. The van had small windows so we could see. I’ve driven up to Seattle before but that was by far the longest car ride up to Tacoma. There were a lot of places that I would have recognized but under the circumstance, nothing felt or looked familiar to me at the time.

That drive brought me a little bit closer to realizing that any day from now I could end up back in Mexico with out being able to do anything about it. That feeling of for the longest time feeling like I’m home, that out of nowhere getting that feeling that I no longer belong here in the US. It was traumatic.

…After that we were led to another big room. It was the size of a gym or a basketball court. Inside this place, there in the middle of it, there was a bunch of bunk beds and all around the walls, against the walls were cells. By the time they got us in this room it was 10:30pm or 11:00 at night. By then everybody is supposed to be asleep and we are literally walking into a dark room. Obviously no one was asleep. I remember some young detainees in their early 20s or even minors were asking us for food.

I was in an upper bunk. We were told to go to sleep. And I remember there was a lot of tossing and turning and I couldn’t fall asleep. I probably feel asleep for about an hour and then woke up thinking it was all a dream and then finally once I was wide awake realizing that I was still in the same place and that it was actually not a dream.

I was in Tacoma for 12 hours but I could see the impact it had on others who had been there for a long time.

That night, it was really quite. They gave us little radios and I figured if I listened to music, that would help me fall asleep quicker. That silence was too much for me so I decided to put on the headphones and listen to music. Just the fact that I was listening to music and the radio kind of brought me back to being out of there and like something I would do as a normal person. The only station that the radio caught was an R&B/Hip Hop station. So, that’s what I listened to that night.

It was the only thing tying me to the outside world. There was nothing else”

Francisco

27-yr-old DACA Recipient

SHERIDAN FEDERAL CORRECTIONS INSTITUTE

Sheridan, Oregon

On May 31, 2018, ICE transferred 124 asylum seekers to this Federal Prison Facility.

According to Innovation Law Lab in Portland, this included people from 16 different countries, speaking 13 different languages.

By November 28, 2018 all 124 asylum seekers had been released on bond, transferred or voluntarily chose deported.

“Day by day, you ask yourself and often wonder When it will be your time to be released? You don’t have a release date and you are waiting until the judge sends an order. It’s hard to sleep because you are wondering, When am I going to leave? Maybe next week? What will happen? It’s an affliction that you pass through while you are waiting. You enter a deep desperation and you start to wonder if all the time that you’ve wasted will be worth it.

“It was 15 days before anyone knew we were being held in Sheridan. I wasn’t able to talk with family and nobody had access to phones. It felt horrible to not be able to communicate with our family or with attorneys or anyone. Those of us who were in immigration custody spent 23 hours in our cells. With time, when attorneys found out we were in Sheridan, we started to receive better treatment.

“When we were permitted to go outside, it felt nice to be able to distract ourselves for a moment and play games. Outside you could see the fields. You could see some people working outside in the fields. You could see cars driving down a road nearby and it made you wonder again, When will I be able to leave? When will I be able to go to those places? It felt like it was better to distract yourself by playing a game like basketball because if you looked at the scenery you started to think about things on the outside more. It makes me sad to think of that place. Sometimes I still have a weight that’s with me.

“Sometimes I dream that I’m detained again. I dream that I am in prison and then I wake up and realize I’m not.

“After some time, you get used to not being inside anymore, but I would say that the nights are usually harder because it’s during the night when you have memories like the guards passing though the prison and lighting up the cells.”

Carlos, 21-yr-old asylum seeker from El Salvador

Detained for 4 months and 2 weeks

DENVER CONTRACT DETENTION FACILITY

Aurora, Colorado

“Back home, my family wanted to kill me because of who I am. All my life I’ve ran from them.

“I made it to Ecuador but after time, I was attacked, robbed and beaten up there. I went to Mexico, stayed in Tapachula then went to Tijuana. Someone helped me and two other guys cross the border but we were immediately arrested by Border Patrol.

“They transferred me to San Luis, Arizona for a week…I was put on a plane and flown to Denver. The flight was full. No empty seats. I was still in shackles on my hands and legs. I had no idea where we were going. I thought we landed at JFK. I asked a guy, Are we at JFK? and he said, No, you’re in Denver.

“In detention another guy from Ghana said, I feel like committing suicide. I said, You should not give up, if you have any hope in you.

“But in detention you are kidnapped. You have no one to turn to. It makes you feel very pathetic.

“In detention what can you think of? You think of everything and you worry. And in the end you remember another you.”

28-yr-old gay man from Ghana

Detained for 5 months

OTERO COUNTY PROCESSING CENTER

Chaparral, New Mexico

“For the management, everything is business. The workers at the detention center would say, You guys are just numbers. You’re just numbers that make money for us.

“They never call you by your name. They call you by your bunk number and they would call your bunk number in Spanish only. I had to learn Spanish. I had no choice. When immigration comes, they call you by your Alien Registration number. Ninety-percent of the time they do it only in Spanish. If your bunk number is four, they would call you, Cuatro. So, to the detention staff you are a ‘bunk number’. To immigration, you are an ‘A number’. You never hear your name.”

41-yr-old man from Nigeria

Detained for 1 year and 2 months

“I presented myself right at the port of entry…I told them I’m coming to the United States to seek asylum because I’m running away from my home government who wants to kill me and my family.

“When I was walking through that tunnel at the US port of entry I thought I was walking towards the gate of freedom. Little did I know, I was walking towards the gate of hell.

“On that fateful day, my hands were cuffed and my legs were chained and I did nothing more than move from process to process to process, all in chains. All in chains.

“I was transferred to Otero without any information. No one told me anything. The system only wants deportation. It was clear. Racism was a part of it because I was a black man who could ask questions. At times, I was shunned. I realized I needed the hand of God to help me because the hand of man would fail me because the rate of which racism was practiced in Otero was alarming.? If anyone wants to know what hell looks like, just come and I’ll tell you what Otero looks like and I will describe to you what the gates of hell look like.”

33-yr-old asylum seeker from Cameroon

Detained for 1 year and 3 months

“When I first leave the facility I feel angry and helpless. I often think of destructive things I can do to lash out. The drive home, about an hour, is often consumed by trying to funnel my anger to more productive ends. Sometimes I am so mad I am quiet, because I’m afraid if I speak I will lose control. I often cry.

“I visited an older gentleman who shook uncontrollably, was glassy-eyed and felt ill. I also visited a young man who seemed to be unbelievably resilient. Another man I visited experienced more mental anguish and emotional turmoil as time went by.

“When we said goodbye he would always bless me, and thank me profusely for being so human toward him. We would both give each other hugging gestures through the glass.”

Margaret

Visitation Volunteer

WEST TEXAS DETENTION CENTER

Sierra Blanca, Texas

“When the first person got off the bus at Sierra Blanca, the officers grabbed him, slammed him against the wall and they hit him in the back of his head with an elbow blow shot. He hadn’t done anything wrong.

“That right there automatically alerted us that these people are going to be on us the whole time we were there.

“Where they put us, it was like a chicken coup. You had to open that cage door and behind that cage door were a bunch of open beds. They closed that cage and they would taunt you behind the cage like we were some kind of animals. There was a lot of verbal abuse going on. We’d ask for something and they’d say, Why do you care, you’re getting deported anyway? Being in Sierra Blanca and going through all of that and knowing it was all going to lead to my deportation, I lost all hope.

“These officers, they followed no type of law. Actually, they would do what they felt like doing to us. We were stuck. They were pretty much hanging us. You had crazy thoughts just trying to figure it all out. Nobody would tell us nothing. When the officers beat all of us up, we were transferred to other detention centers. I’ve now been in ICE custody for 13 months.”

31-yr-old asylum seeker from Somalia

Detained for 13 months

SOUTH TEXAS RESIDENTIAL CENTER

Dilley, Texas

EL PASO SERVICE PROCESSING CENTER

El Paso, Texas

“There was an officer at the detention center in El Paso. He was homophobic and he made my life impossible.

“He would threaten me and warn me that he would put me in a room called ‘the wolf’ where there is no light. You can’t see anything, and you can’t speak to anyone. You stay in there for 15 days. They would say things as if you were not a person. It’s like you feel like you don’t exist. Like you have no worth. Day after day these were the experiences that make you want to just give up.”

Jose, 21-yr-old asylum seekers from El Salvador

Detained for 9 months in three different locations

in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas

“The experience of providing legal support to asylum seeking parents detained in the El Paso Processing Center (where no processing seems to ever happen) is an assault on the senses.

“Every sound echoes, and the most consistent sound is that of keys jingling as the guards pace halls I cannot see.

“The air smells dead – not even the odor of the disinfectant that I think they must hose the rooms down with at night. And the softest thing in the room are the tissues I hand to each parent.

“In a bare, sterile room behind three individually locked doors, I am allowed to provide volunteer legal assistance to asylum seeking parents that have been separated from their child, and then detained for months. In more than two dozen such meetings, each individual was subdued – no sudden movements, downcast eyes, quiet voices. Many, many officials they had dealt with in that time had formed their attitude. Many were lied to, coerced, had cruelty aimed at them, and were emotionally crumpling from the toll. Yet every single one voluntarily laid their heart in my hands, told me their story, answered my questions, and asked nothing from me.”

Susanne

Immigration Attorney

KARNES COUNTY RESIDENTIAL CENTER

Karnes, Texas

“The border patrol told me that my son would be taken to a secure place and they told me, You, you’re going to jail!

“It was something I never thought could happen and I could never imagine. I wasn’t sure where they would be taking my son. He had just turned 8-years-old when we were separated…Moments later an officer came in. That was perhaps the most painful moment, when they were handcuffing me in front of my son. He could see me through a glass door. I tried to make signs with my hands to him through the glass door. I tried to put my hands down to say to my son: Calm...Calm. To say everything was fine.

“All of this was happening to a group of families. About 25 in total. Fathers and mothers with children. We were all worried, not knowing where we were going or where our children were being taken. There was crying. Mostly the mothers. And then they took us away.

“I was taken to Otero Detention Center. I was there for six days. I had no idea where my son was at this time. After Otero, we thought we would be reunited with our children. But then it turned out when we got there, it was Cibola, which is another detention center. In Cibola, I found out my son was in San Antonio but I couldn’t talk with him because I didn’t have any money.

“After 20 days in Cibola they took e to El Paso. After fifteen days in El Paso, I was finally able to talk with my son on the phone. He sounded different. He was sad and he was so quite. I needed to hug him. I needed to see him, but I couldn’t.

“They gave my son back to me in El Paso. Then they transported us by bus from El Paso to Karnes. We were told we were going to be taken to a place where we would spend the night and that we were going to be reunited with our family in the US. During the bus ride, I had my hands free and my son by my side. I fell asleep with him in my arms.

“In Karnes, there were always officers around. They would tell us, Be careful. They would come to our rooms and check on us. At night they would also check on us. We had a schedule when we had to report and present ourselves. We had strict eating hours. There was always some sort of officer watching us to see if we were behaving well or if we were behaving poorly. Some officers at Karnes would tell me how to care for my son. To not hit my son. To go to medical. To not think bad things. To not think of taking my own life. They said this to all the families there. It was uncomfortable. You always had someone behind you, demanding you to clean and do things well but it was different because at least I had my son with me and I felt I had to just get through it.

“Fifteen days after we arrived at Karnes we saw on the news that the President had said something about all of us being indefinitely detained. This was the lowest point for many of us. We were full of anguish.

“Detention made me very depressed and full of stress. I now have a great problem with nervousness. I try to control it and I try to get a lot of help with this anguish because there is still a very great fear that remains in my mind. It feels as if I am still detained. This fear. It’s a great trauma.

“My son is still adjusting. His character changed. He’s much more reserved. We’ve been trying to talk to him. To tell him not to worry. That we won’t be separated again. He is still very timid. He is still very quite and he still has that sense of sadness.”

33-yr-old asylum seekers from Honduras

Separated from his 8-yr-old son in May 2018 for 45 days

Detained for 6 months (4 months with his son)

“They put me on a bus and took me to Port Isabel detention center...This whole time, I was thinking I was about to be reunified with my son...instead they transferred me to a detention center in Houston. I was there for 58 days... I wasn’t permitted to communicate with him for over one month. While in Houston, I was finally able to speak with him. I spoke with him only two times. That was it.

“The first time was on his 16th birthday. Both of us were so happy to be able to speak. I wish I could have seen him in person on his birthday but I knew it couldn’t be. He said, I feel stressed and worried. When are they going to take us out of here? I know my son and I know when he is worried and happy in his voice and I could hear the worry in his voice over the phone. It was very difficult hanging up that phone call.

“The hardest part for us in Karnes was that we were there for so long. We would see other families that had also been separated from their children and who were finally getting released together. But we remained there in Karnes and be asking, Why not us? Why us? Why are we still here?

“We saw many people who were at the point of asking for their deportation or trying to decide if they should ask for their deportation or continue with their case. We always put our faith in God. That God would push the hands of the government. So we continued.

“My son is generally less active now. I don’t know if it is being in a new country or if it is because of what happened to him in detention but I see him with less motivation to be active. He has less desire to be active than he was before. That experience in detention for us is inerasable from our minds. It will always be with us.”

Bernabe, 45-yr-old asylum seeker from Honduras

Separated from his 15-yr-old son in May 2018 for 2 months

Detained for 6 months (4 months with his son)

T. DON HUTTO RESIDENTIAL CENTER

Taylor, Texas

“Only women are detained in Hutto. I had so many questions because I didn’t know how long I would have to spend there and I was so afraid. I was there for over four months. The first couple of days I was so depressed. It was a very lonely place. I felt invisible. People see us as if we don’t have any human rights. We felt like we should not be in there. There are good days and there are bad days. Sometimes you can tolerate it. Some days you feel like you can’t take it anymore. There were days when I felt like I would just give up.

“Every cellblock had 20 cells and every cell has two beds. It was overwhelming. You can’t do anything without permission or someone watching you. Every time you walk, you have to tell them where you are going. The state of mind of people who are being held there is terrible. There are so many who try to commit suicide. Because of that, they watch us so intensely. I felt like I was asphyxiated, like I was suffocating.

“I had a cellmate. We became friends. She had already been in detention for over eight months when I got there. Her depression was so bad. There were ten cells on the ground level and then another ten cells on the floor above. A couple of times her depression got so bad she tried to jump off the second floor because she just couldn’t take being detained anymore. After eight months being held there, she never received positive answers to her asylum case. She got really depressed and it drove her to wanting to kill herself.”

25-yr-old woman asylum seeker from Nicaragua

Detained for 4 1/2 months

“I worked in the laundry at the detention center and one day while I was working I told the officer I didn’t feel well and asked if I could go back to my cell. That night, I fainted and I don’t remember anything until I woke up in the hospital.

“I stayed in the hospital for 15 days. During those 15 days, the officers from the detention center would not leave my sight. There were two officers in my room all the time: one man and one woman, always wearing their uniforms: dark green shirts and khaki pants. At 6:00pm everyday, the ones who where there in the morning would leave and two new officers would replace them for the night. The officers were always there. All the time.

“They wouldn’t let the doctors or the nurses be there with me alone. The officers wouldn’t talk to me. They didn’t say a word. They had a notebook where they would write down everything I did in it: what I ate, when I went to the bathroom, when I took my medicines. At night, while I was sleeping, they were there in my room. Even while I would take a shower. One of them would stand there in the door of the bathroom while I showered. I was never alone. They were all over me.

“The day I was released from the hospital, they made me put on my uniform from the detention center: a dark-blue shirt and light-blue pants. They put me in handcuffs and I was refrained around my waist. My feet were shackled. Then they took me out of the hospital in a wheelchair.

“When I was in the wheelchair and they were taking me out of the hospital, I was crying and humiliated. I was thinking about everything I had gone through just to come to the US. They took me out of the hospital like I was a criminal. People looked at me in the wheelchair and no one showed compassion toward me knowing I was sick and seeing me be taken out to the van in that way. They put me in the van and took me back to Prairieland.”

27-yr-old woman asylum seeker from El Salvador

Detained for 1 year and 4 months in three

different detention centers

PRAIRIELAND DETENTION CENTER

Alvarado, Texas

SOUTH TEXAS DETENTION CENTER

Persall, Texas

“What first struck me when I visited was the heaviness I sensed when speaking with individuals, specifically the heaviness of meeting with a person who was deprived of their freedom.

“My clients have survived significant trauma and persecution in their home countries. Yet, they come to the U.S. and for many of them, it is here, inside our immigrant detention centers, where they reach their breaking point.

“I often feel great guilt leaving a person after a meeting. I leave them in the center, which looks and feels like a prison, because it is a prison, with its cinder-block walls and barbed wire.

“I am constantly struck by the great effort that is taken to dehumanize each individual. From the color-coded wardrobe each detainee must wear: blue, orange, red, to the use of their alien number rather than their name. They have such courageous stories but the system is designed in such a way as to silence their bravery.

“I spend many hours in the lobby, waiting to meet with clients. As I sit in the lobby I observe family and friends of detainees enter. Many have traveled hours, via car or plane. Some go to court to witness the fate of their loved one. Unfortunately, I see many family members leave weeping. I wonder how painful that must be, for an individual to see their spouse, or child through a glass window, to be so close to them, yet be deprived of their embrace.

“Despite all the injustices I witness, it is my own clients who encourage me to keep fighting. I have never experienced such courage and gratitude then when I am working alongside my clients. If they have the will to keep fighting, how can I not join them?”

Priscilla

Immigration Attorney

“For me, it got to the stage where I myself...it was the last thing I wanted to do...be deported, but I voluntarily asked to be deported. There was no need to spend another 3 years in detention for a federal appeal of my case. My life has been destroyed. My family has been destroyed. Let me go back.

“The entire system is corrupt. It dehumanizes people. And, it is money making.

“They want to keep you isolated from the world so that no one knows if you exist or if you die. In my country, people who are locked up in prison are the bad guys in society. So, just being locked up in a prison is enough to bring some psychological impact on me. Seeing myself in prison clothes, there was just no more dignity in me. I ask myself, Have I come to fight with the United States? Am I a rebel? Am I a terrorist?...I am none of the above! My country never fought a war with the United States. I’m not a prisoner of war. So why would they treat me like this? To my surprise, nobody could understand us. ICE is inhuman. They don’t have a heart of a human being.”

38-year-old asylum seeker from Sierra Leone

Detained for 1 year and 8 months

TORNILLO TENT CITY

Tornillo, Texas

Immigrant Children Shelter

Company: BCFS Health & Human Services (Non-profit status)

Capacity: 1,575 (In December 2018 it held up to 3,000 children)

From June 2018 to mid-January 2019 some 6,000 children where held here

Closed in mid-January 2019

BLUEBONNET DETENTION CENTER

Anson, Texas

STEWART DETENTION CENTER

Lumpkin, Georgia

ADAMS CORRECTIONAL CENTER

Natchez, Mississippi

PINE PRAIRIE ICE PROCESSING CENTER

Pine Prairie, Louisiana

“I’m in this meeting with the ICE Assistance Field Officer and the warden of Pine Prairie and they said, You know we have a contract with GEO and we try to be really good partners and we try to make sure that they always have enough inventory right here. Inventory meaning, people.

“The amount of like depression, anxiety that you see from people in these detention centers is just out of this world and it makes so much sense, I mean, they are held in these conditions, apart from their loved ones, lack of freedom, treated as if they weren’t human. And number one, like that might have long lasting psychological impacts on people and I’ve certainly seen as s general rule, the longer someone is in detention, the worse mental state they end up in. That’s one thing but in terms of their case as well, on month three of a case the average person has a lot more, kind of like, spirit and ability to fight than on month 24 or month 36 and this detention, this isolation, really takes a toll on people. On average, a rough estimate it will take 6-7 months to fight your initial case, then if you appeal it, that’s like another 7-8 months, and right there you are already at a year, and so a lot of this stuff can happen. And let’s say you win your case and you have to have a new trial, well that’s another 6 months. A lot of the time, ICE and the immigration courts aren’t in any hurry so that delays stuff as well.

“I had this one client who, he was a mechanic and he had all these youth programs and was doing all of this youth mentoring and then ICE picks him up, he’s detained for 5 years while he fights his case and then deported and the pain in this guys face when he’s telling me or he’s telling the judge about how he hasn’t seen his children in so long and about how they are growing up without him an about how he would just give about anything just to talk with them again, that’s the kind of stuff that will stick with you forever. And that really underscores why we really can’t have this system, right? That’s one guy but this is happening to thousands and thousands, like there are thousands of versions of that on any given day.”

Jeremy

Immigration Attorney

SOUTH LOUISIANA DETENTION CENTER

Brasile, Louisiana

CENTRAL LOUISIANA ICE PROCESSING CENTER

Jena, Louisiana

RIVER CORRECTIONAL CENTER

Ferriday, Louisiana

NORTHEAST OHIO CORRECTIONAL CENTER

Youngtown, Ohio

“In my view, there was no other place better than the United States, the land of the Free and Prosperity. I have been in ICE custody for a long time. It has been over 2-years since I was put in detention and only God knows if I will be released or deported back to my country of origin. In my time in incarceration only God knows what I have been through…Degradation, Humiliation, Deprivation, Dehumanization and more…It should have been a civil detention but I and my fellow immigrants have been treated as criminals.

“I have been away from my family. I lost my WIFE and rarely talk to them because it’s hard and costly. Everything here in prison is compromised: food, medicine and treatment. Almost all the time we are held in the units, counting happens all the time and there is lockdown 5 times a day. Being in prison has impacted me in various ways including emotionally, physically and mentally. I will say not spiritually.

Loss of freedom, constantly being monitored, being separated from family, friends and the outside world and not knowing if you would be released or being deported back to your country…that feeling is the story of my time in prison the United States Prison.”

25-yr-old asylum seeker (undisclosed country)

Detained for 2 years and 2 months

“Two days ago I was able to convince a judge to give my client a little more time to prepare his case. My client was happy I could help him. But there’s so much he doesn’t know.

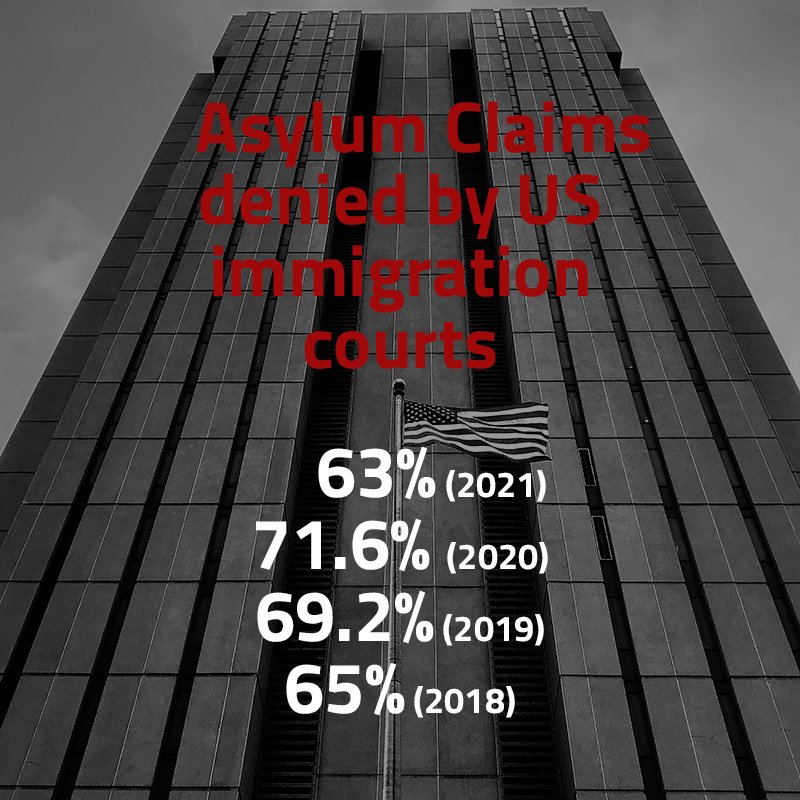

He doesn’t know that statistically his chances of ever getting out of detention are slim to none, that his odds of ever actually winning asylum are even more remote. He doesn’t know that hundreds of miles away in our nation’s capital powerful, educated, highly-paid government lawyers are right now discussing strategies to make his case even harder to win, to make it even less likely he will ever walk free here in the U.S.., indeed to make it less likely that people like him will ever even make it out of their collapsing home countries.

He doesn’t know that he’s trapped inside a giant wealth transfer machine that ruthlessly nickels-and-dimes working-class Americans and asylum seekers alike in order to enrich shareholders who will never in their lives see the inside of a prison, or know hunger, or find themselves in need of asylum.

All he knows is that for the first time since he left his country and spent weeks crossing Mexico barefoot, with no money and no food, for the first time someone is on his side. Knowing only this, he’s happy. But I know all the things he doesn’t know, and I’m sad.”

Brian

Immigration Attorney

ELIZABETH CONTRACT DETENTION CENTER

Elizabeth, New Jersey

“When I arrived at JFK I told them I’m seeking asylum. They first told me they wanted to deport me back. I told them I can’t go back! So they told me they were going to take me to a place where I’m going to stay for some time and wait for a judge.

“When they opened the doors at Elizabeth, I didn’t know where I was at first. I didn’t even know it was Elizabeth or anything. I was still in handcuffs and they told me to go into the check in room. I was crying. I was frustrated. I was crying so much. They tried to calm me down...They brought me a uniform and took me to a room and told me to remove everything like take off all my clothes. It was very very overwhelming. I cried so much because I was being treated like a I was a prisoner.

“I was wearing a prison uniform. They took me to the dormitory and I dropped down when I reached the dormitory. There were other girls in the dorm. It has 29 beds…The girls I met tried to calm me down. They tried to talk to me, Don’t worry, everything is going to be fine. You’re going to be there for some time, but don’t worry. We’ve been here for this long.

“Wearing a uniform, it’s so overwhelming. Those are things you only see in movies. But seeing it happen to you is really devastating. You just can’t believe that you are falling out of a cistern and into the fire. You can’t be sure of what you are doing. You can’t be sure of how long you’re going to be there. You can’t be sure of what the judge is going to tell you. You can’t be sure if you are going to win your case. You’re not sure. In everything, you have to wait and be patient and look up and know you will be in there for quite some time.”

29-yr-old woman asylum seeker from Uganda

Detained for 5 months

“I would say at that time, I really felt empty. My heart was empty. I saw that I escaped death in my country but I came to find again here because I was in a jail. I’ve never been in jail. I’ve never committed a crime so it overwhelmed me. I thought anything would happen…I never felt like a human being. Not ever one day. You are reduced to nothing.

“The bad part of it is that it is life lasting. Until now…I’ve never healed from that experience. I’ve never healed from life in detention. I don’t know when I will.

“Today, I will always still see myself as different than others. Very, very different from others and it makes me very afraid of everybody. It has reduced my trust in people because I’m just afraid, I’m just afraid of everything. Sometimes, I just prefer being alone in my room and just by myself which is not good and while I’m waiting, the thoughts come back again.”

Asylum seeking woman from central Africa

Detained for several months

FARMVILLE DETENTION CENTER

Farmville, Virginia

“After we were in the freezers at the border, they took us to a jail. They would read off group names on the list and one day my name was on one of those lists. They too me out of the jail with some others, boarded us on a plane without us knowing that we would go to Virginia.

“I felt like it was over. That I was going to be deported. They put shackles on my wrists and legs and waist and made us board the plane. It was a big plane. Packed with about 100 people. I sat on the window…I was emotional because it was the first time I was going to fly but there was a lost hope by looking at everyone on the plane shackled and sitting in their seats.

“When we got off the plane, they packed us into two buses and when I was arriving I was under the impression it was a jail and that we would be there for a few days where they would prepare to deport us.

“For two months, they did not allow us to go outside because it was snowing out and it was too cold. When that passed away, we were allowed to go out. I felt some hope but I knew it wouldn’t last long.

“After the fifth month in detention, I was losing hope. There’s a lot of desperation. There was an ICE officer who would come and tell us that if we went through the immigration process without representation, it would be very difficult to convince a judge. They said to get an attorney.

“I felt powerless like I was pinned against a wall because the attorneys were charging $2500 USD for representation and I didn’t have the money and my family didn’t have it either. It drove me to think I would need to go about the process by myself. Then I met some pro bono lawyers. I know I would have lost my case without them.

32-yr-old asylum seeker from Honduras

Detained 6 months

“Farmville is three and a half hours from Washington, DC so you feel like you are going far away and once you get off the highway you’re going through farm country in south Virginia. You get farther and farther away until you come to a small town and Farmville itself, is set back on a piece of property. You can’t see it from the road and then it looks like a cinderblock, large, nondescript, cold building.

“It’s just heartbreaking that people who have really not done bad things in our country are sitting in these detention centers…slash…jails, separated from their families. I feel that what I can offer on the hotline is a word of caring, of a person calling them by their name, having them hear my voice and recognizing that someone is there. What they are making phone calls to the hotline about is really a lifeline to getting out from where they are and that conversation, that voice of trust and the sense that somebody is really listening to me, somebody seems to know my name, and is caring about me. I think that is the conversation that gives them more hope.

“Desperation is the one emotion I feel the most from them and I wish I could say to everyone one of them, That’s alright, we can find you a lawyer, don’t worry. But of course, you can’t ever say that.”

“I have sleepless nights, bad dreams and I worry.

Susan

Volunteer on a non-profit immigration detention hotline call in program.